AGATHA CHRISTIE SOLVES THE MYSTERY OF SURFING: "IT IS ONE OF THE MOST PERFECT PHYSICAL PLEASURES THAT I HAVE KNOWN"

Agatha Christie, the British-born "Queen of Crime," whose collective works have outsold everyone but Shakespeare and God's own Bible-writing ghostwriters, was part of a 10-month worldwide Grand Tour, along with her husband Archie, in 1922, to promote the upcoming British Empire Exhbition. Christie was 31 and had published her first two mysteries, but was not yet the international crime-writing giant she would become.

The seven-member Empire Exhibition group sailed by steamer from Southampton to Cape Town, South Africa, a 16-day journey. From there, it was on to Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Canada. Christie and her husband both surfed in the South African resort town of Muizenberg, not far from Cape Town, and again in Waikiki. The quotes below are taken from Agatha Christie: an Autobiograry, published in 1977, one year after Christie's death at age 86.

* * *

FEBRUARY

Going round the world was one of the most exciting things that ever happened to me. It was so exciting that I could not believe it was true. I kept repeating to myself, "I am going round the world." The highlight, of course, was the thought of our holiday in Honolulu. That I should go to a South Sea island was beyond my wildest dream. It is hard for anyone to realize how one felt then, only knowing what happens nowadays. Cruises, and tours abroad, are a matter of course. They are arranged reasonably cheaply, and almost anyone appears to be able to manage one in the end.

When Archie and I had gone to stay in the Pyrenees, we had traveled second-class, sitting up all night. (Third class on foreign railways was considered to be much the same as steerage on a boat. Indeed, even in England, ladies traveling alone would never have traveled third class. Bugs, lice, and drunken men were the least to be expected if you did so, according to Grannie. Even ladies’ maids always traveled second.) We had walked from place to place in the Pyrenees and stayed at cheap hotels. We doubted afterwards whether we would be able to afford it the following year.

Now there loomed before us a luxury tour indeed. Nothing but the best was good enough for the British Empire Exhibition Mission. We were what would be termed nowadays VIPs.

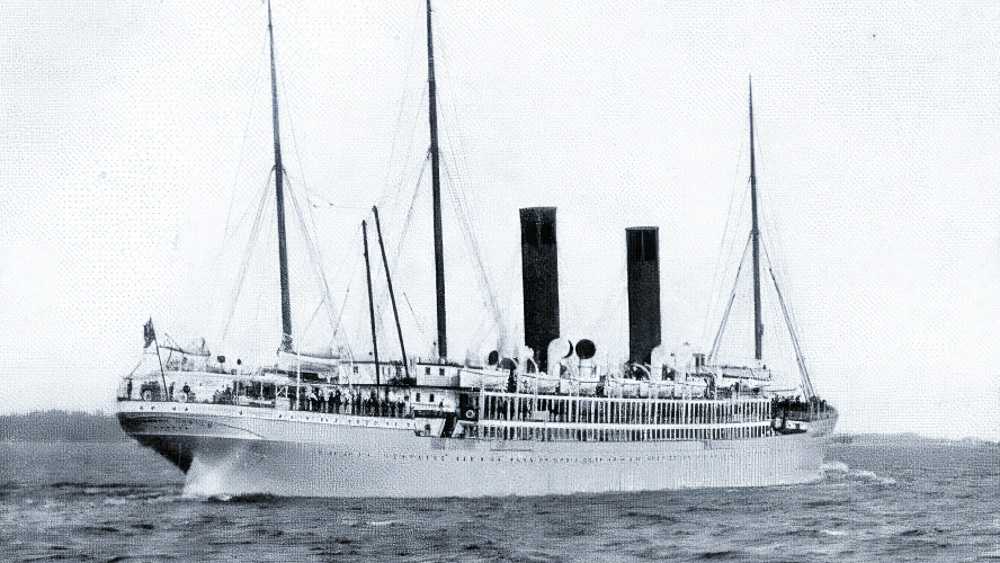

Although we started out in such high spirits, my enjoyment at least was immediately cut short. The weather was atrocious. On board the Kildonan Castle everything seemed perfect until the sea took charge. The Bay of Biscay was at its worst. I lay in my cabin groaning with sea-sickness. For four days I was prostrate, unable to keep a thing down. In the end Archie got the ship’s doctor to have a look at me. I don’t think the doctor had ever taken sea-sickness seriously. He gave me something which "might quieten things down," he said, but as it came up as soon as it got inside my stomach it was unable to do me much good. I continued to groan and feel like death, and indeed look like death; for a woman in a cabin not far from mine, having caught a few glimpses of me through the open door, asked the stewardess with great interest: "Is the lady in the cabin opposite dead yet?"

By the time we arrived [in Madeira] I was so weak that I couldn’t even contemplate getting off the bed. In fact I now felt that the only solution was to remain on the boat and die within the next day or two. After the boat had been in port about five or six hours, however, I suddenly felt a good deal better. The next morning out from Madeira dawned bright and sunny, and the sea was calm. I wondered, as one does with sea-sickness, what on earth I had been making such a fuss about. After all, there was nothing the matter with me really; I had just been sea-sick. There is no gap in the world as complete as that between one who is sea-sick and one who is not. Neither can understand the state of the other.

My memories of Cape Town are more vivid than of other places; I suppose because it was the first real port we came to, and it was all so new and strange. The Kaffirs, Table Mountain with its queer flat shape, the sunshine, the delicious peaches, the bathing—it was all wonderful. I have never been back there—really, I cannot think why. I loved it so much.

This is no travel book—only a dwelling back on those memories that stand out in my mind; times that have mattered to me, places and incidents that have enchanted me. South Africa meant a lot to me. My memory brings back to me hot dusty days in the train going north through the Karroo, being ceaselessly thirsty, and having iced lemonades. I remember a long straight line of railway in Bechuanaland. The Matopos I found exciting, with their great boulders piled up as though a giant had thrown them there.

At Salisbury we had a pleasant time among happy English people, and from there Archie and I went on a quick trip to the Victoria Falls. I am glad I have never been back, so that my first memory of them remains unaffected. Great trees, soft mists of rain, its rainbow coloring, wandering through the forest with Archie, and every now and then the rainbow mist parting to show you for one tantalizing second the Falls in all their glory pouring down. Yes, I put that as one of my seven wonders of the world.

We went to Livingstone and saw the crocodiles swimming about, and the hippopotami. From the train journey I brought back carved wooden animals, held up at various stations by little native boys, asking three-pence or sixpence for them. They were delightful. I still have several of them, carved in soft wood and marked, I suppose, with a hot poker: elands, giraffes, hippopotami, zebras— simple, crude, and with a great charm and grace of their own.

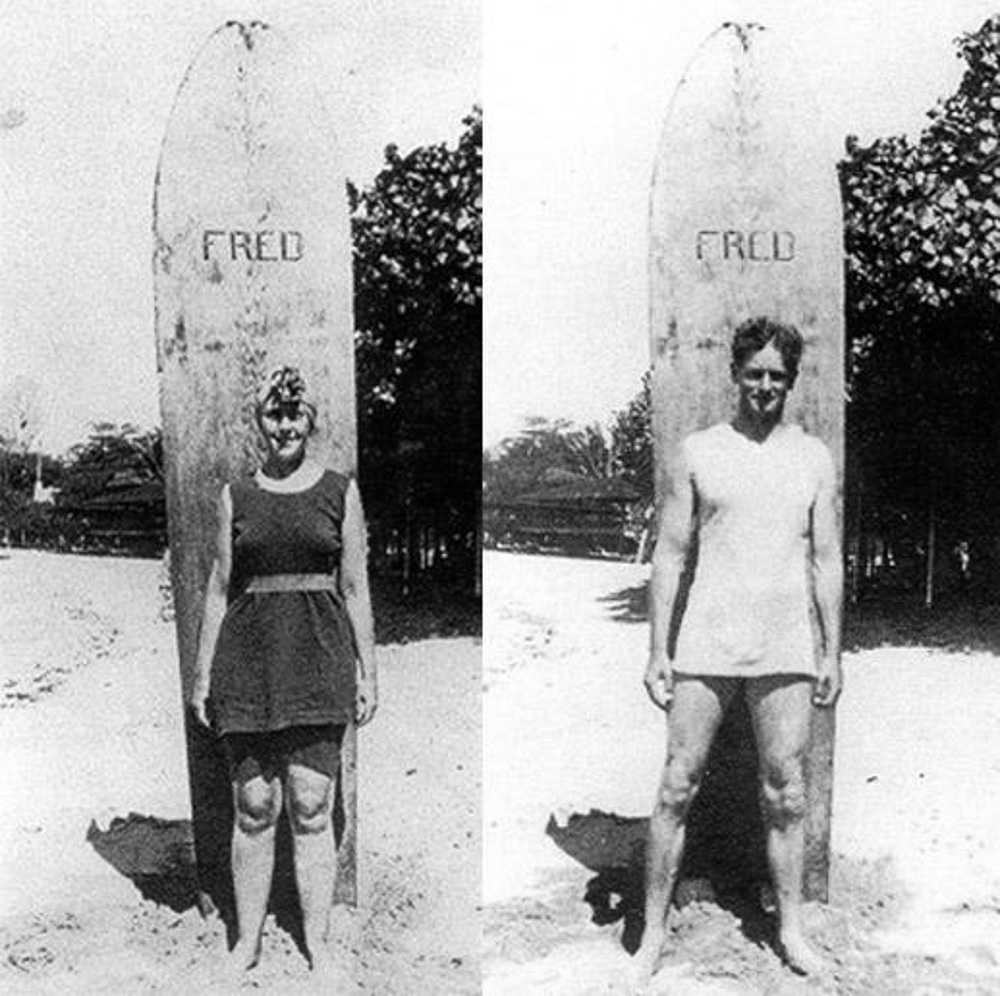

We went to Johannesburg, of which I have no memory at all; to Pretoria, of which I remember the golden stone of the Union Buildings; then on to Durban, which was a disappointment because one had to bathe in an enclosure, netted off from the open sea. The thing I enjoyed most, I suppose, in Cape Province, was the bathing. Whenever we could steal time off—or rather when Archie could—we took the train and went to Muizenberg, got our surfboards, and went out surfing together.

The surfboards in South Africa were made of light, thin wood, easy to carry, and one soon got the knack of coming in on the waves. It was occasionally painful as you took a nose dive down into the sand, but on the whole it was easy sport and great fun. We had picnics there, sitting in the sand dunes. I remember the beautiful flowers, especially, I think, at the Bishop’s house or Palace, where we must have been to a party. There was a red garden, and also a blue garden with tall blue flowers. The blue garden was particularly lovely with its background of plumbago.

* * *

AUGUST–SEPTEMBER

We had a lazy voyage, stopping at Fiji and other islands, and finally arrived at Honolulu. It was far more sophisticated than we had imagined, with masses of hotels and roads and motor-cars. We arrived in the early morning, got into our rooms at the hotel, and straight away, seeing out of the window the people surfing, we rushed down, hired our surfboards, and plunged into the sea. We were, of course, complete innocents. It was a bad day for surfing—one of the days when only the experts go in—but we, who had surfed in South Africa, thought we knew all about it. It is very different in Honolulu. Your board, for instance, is a great slab of wood, almost too heavy to lift. You lie on it, and slowly paddle yourself out towards the reef, which is—or so it seemed to me—about a mile away. Then, when you have finally got there, you arrange yourself in position and wait for the proper kind of wave to come and shoot you through the sea to the shore. This is not so easy as it looks. First you have to recognize the proper wave when it comes, and secondly, even more important, you have to know the wrong wave when it comes, because if that catches you and forces you down to the bottom, Heaven help you!

I was not as powerful a swimmer as Archie, so it took me longer to get out to the reef. I had lost sight of him by that time, but presumed he was shooting into shore in a negligent manner as others were doing. So I arranged myself on my board and waited for a wave. The wave came. It was the wrong wave. In next to no time I and my board were flung asunder. First of all the wave, having taken me in a violent downward dip, jolted me badly in the middle. When I arrived on the surface of the water again, gasping for breath, having swallowed quarts of saltwater, I saw my board floating about half a mile away, going into shore. I myself had a laborious swim after it. It was retrieved by a young American, who greeted me with the words: "Say, sister, if I were you I wouldn’t come out surfing today. You take a nasty chance if you do. You take this board and get right into shore now." I followed his advice.

Before long Archie rejoined me. He too had been parted from his board. Being a stronger swimmer, though, he had got hold of it rather more quickly. He made one or two more trials, and succeeded in getting one good run. By that time we were bruised, scratched, and completely exhausted. We returned our surfboards, crawled up the beach, went up to our rooms, and fell exhausted on our beds. We slept for about four hours, but were still exhausted when we awoke. I said doubtfully to Archie: "I suppose there is a great deal of pleasure in surfing?" Then sighing, "I wish I was back at Muizenberg."

The second time I took the water, a catastrophe occurred. My handsome silk bathing dress, covering me from shoulder to ankle was more or less torn from me by the force of the waves. Almost nude, I made for my beach wrap. I had immediately to visit the hotel shop and provide myself with a wonderful, skimpy, emerald green wool bathing dress, which was the joy of my life, and in which I thought I looked remarkably well. Archie thought I did too.

We spent four days of luxury at the hotel, and then had to look about for something cheaper. In the end we rented a small chalet on the other side of the road from the hotel. It was about half the price. All our days were spent on the beach and surfing, and little by little we learned to become expert, or at any rate expert from the European point of view. We cut our feet to ribbons on the coral until we bought ourselves soft leather boots to lace round our ankles.

I can’t say that we enjoyed our first four or five days of surfing—it was far too painful—but there were, every now and then, moments of utter joy. We soon learned, too, to do it the easy way. At least I did—Archie usually took himself out to the reef by his own efforts. Most people, however, had a Hawaiian boy who towed you out as you lay on your board, holding the board by the grip of his big toe, and swimming vigorously. You then stayed, waiting to push off on your board, until your boy gave you the word of instruction. "No, not this, not this, Missus. No, no, wait—now!" At the word "now" off you went, and oh, it was heaven! Nothing like it. Nothing like that rushing through the water at what seems to you a speed of about two hundred miles an hour; all the way in from the far distant raft, until you arrived, gently slowing down, on the beach, and foundered among the soft flowing waves. It is one of the most perfect physical pleasures that I have known.

After ten days I began to be daring. After starting my run I would hoist myself carefully to my knees on the board, and then endeavor to stand up. The first six times I came to grief, but this was not painful—you merely lost your balance and fell off the board. Of course, you had lost your board, which meant a tiring swim, but with luck your Hawaiian boy had followed and retrieved it for you. Then he would tow you out again and you would once more try.

Oh, the moment of complete triumph on the day that I kept my balance and came right into shore standing upright on my board!

We proved ourselves novices in another way which had disagreeable results. We completely underestimated the force of the sun. Because we were wet and cool in the water we did not realize what the sun could do to us. One ought normally, of course, to go surfing in the early morning or late afternoon, but we went surfing gloriously and happily at midday—at noon itself, like the mugs we were—and the result was soon apparent. Agonies of pain, burning back and shoulders all night—finally enormous festoons of blistered skin. One was ashamed to go down to dinner in an evening dress. I had to cover my shoulders with a gauze scarf. Archie braved ribald looks on the beach and went down in his pajamas. I wore a type of white shirt over my arms and shoulders. So we sat in the sun, avoiding its burning rays, and only cast off these outer garments at the moment we went in to swim. But the damage was done by then, and it was a long time before my shoulders recovered. There is something rather humiliating about putting up one hand and tearing off an enormous strip of dead skin.

* * *

Our holiday drew to a close, and we sighed a good deal at the thought of resuming our servitude. We were also growing slightly apprehensive financially. Honolulu had proved excessively expensive. Everything you ate or drank cost about three times what you thought it would. Hiring your surfboard, paying your boy—everything cost money. So far we had managed well, but now the moment had come when a slight anxiety for the future entered our minds. We had still to tackle Canada, and Archie’s £1000 were dwindling fast. Our sea fares were paid for already so there was no worry over that. I could get to Canada, and I could get back to England. But there were my living expenses during the tour across Canada. How was I going to manage? However, we pushed this worry out of our minds and continued to surf desperately whilst we could. Much too desperately, as it happened. I had been aware for some time of a bad ache in my neck and shoulder and began to be awakened every morning about five o’clock with an almost unbearable pain in my right shoulder and arm. I was suffering from neuritis, though I did not yet call it by that name. If I’d had any sense at all I should have stopped using that arm and given up surfing, but I never thought of such a thing. There were only three days to go and I could not bear to waste a moment. I surfed, stood up on my board, displayed my prowess to the end.