"BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOGRAPHY," PATRICK MCNULTY (1967)

SURFER editor Patrick McNulty wrote this editorial for the March 1967 issue. The photo it refers to ran in an article titled "Crocodiles, Zulus, and Surf Suid Afrika," by Ron Perrott, from the May 1966 issue. This version has been slightly edited.

* * *

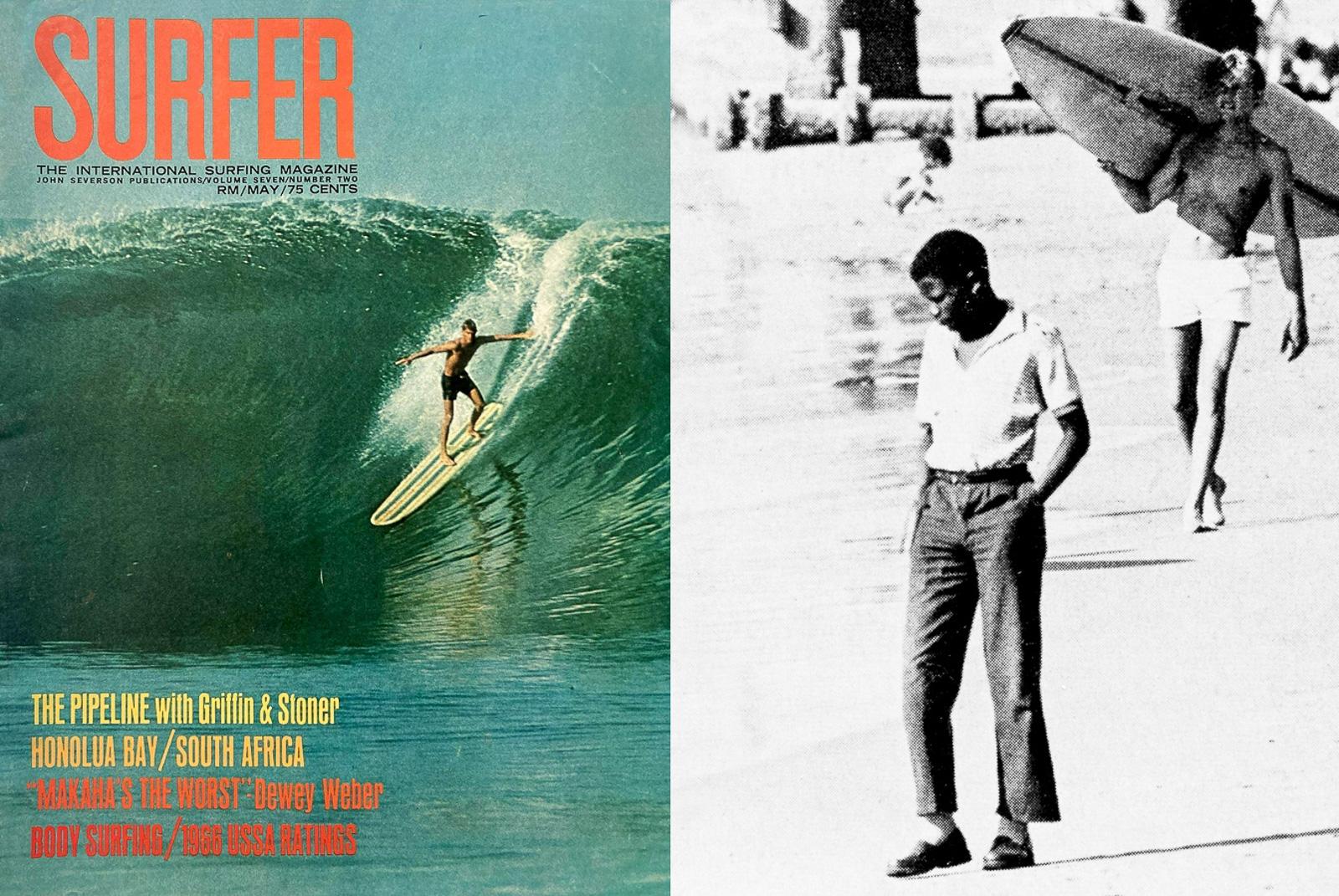

Strangely, the picture that has produced the most reader response over the years had nothing to do with surfing. It was a shot that ran as part of the coverage of South African surfing. The caption simply stated “Durban’s beaches are segregated so this native youngster can’t join these three surfers for a little fun in the surf.”

Response was tremendous. Letters poured into Surf Post. Many readers were critical of any policy of racial discrimination. Others—mostly from South Africa — defended the philosophy of keeping races separated. From Johannesburg, Keith Hosking demanded: “Why don’t you guys think before writing such trash?”

The South African position, essentially, is that Negroes are afforded separate but equal surfing facilities and besides blacks don’t like surfing anyway. Some Americans agreed. From Jacksonville, Florida, Jackson Lanhart, said: “The beaches are practically segregated here in Jacksonville: the whites stay with the whites, and the blacks with the blacks—this way everybody’s happy.”

A dissenting opinion came from Cecil Robbins II, who does most of his surfing at Southampton, Long Island. Robbins wrote:

“I am a Negro surfer—so what would happen if I and a group of my white friends go to Durban? I can’t see any reason why I’d have to troop 200 yards down the beach just because I’ve got more pigment in my skin and a coarser grade of hair! That’s not white supremacy—it’s stupidity.”

So what does all this have to do with surfing?

The photographer who took the picture—SURFER’S roving Ron Perrott—gave this reason: “The critics all lost sight of the key word in the caption—‘JOIN.’ SURFER is an international magazine read by surfers of many races. If there is any restriction—whether political, religious, or local—that hinders the free movement of any surfer, and if this regulation affects surfing or beaches, obviously it must be mentioned.”

The concern of all of us—whether surfers or not—for human dignity and equality should not be confined to Durban or Watts or Grenada, Mississippi. We live in a world made incredibly small by the intercontinental ballistic missile. What happens in Cicero, Illinois, on the sweaty banks of the Congo River, or at Dairy Beach in Durban can affect all of us—whether we’re paddling surfboards or not. Since more and more countries are acquiring the ultimate weapon and the means to deliver it, mankind soon may face the dilemma of living together peacefully—or not living at all.

Even so, SURFER’s concern is with only one small aspect of living—surfing. And that brings us to the point of this editorial.

SURFER has always fought any force that would hamper any surfer from enjoying his sport anywhere in the world. Therefore when a surfer is excluded from a surfing break for any reason—whether at Dairy Beach, the Trestle, or Ocean City, New Jersey—SURFER will call attention to this injustice.

And, incidentally, a good tan has always been a status symbol in the sunny world of surfing. So a dark skin pigment is perhaps the weakest reason for limiting a surfer’s activity in the water.