"THE LAST CAMPER," ANTHONY VAN DEN HEUVEL PROFILE BY CHRIS MAURO (SURFER, 2003)

"The Last Camper," Chris Mauro's feature on Anthony "Doc" van den Heuvel, ran in the November 2003 issue of SURFER Magazine. This version has been slighted edited.

* * *

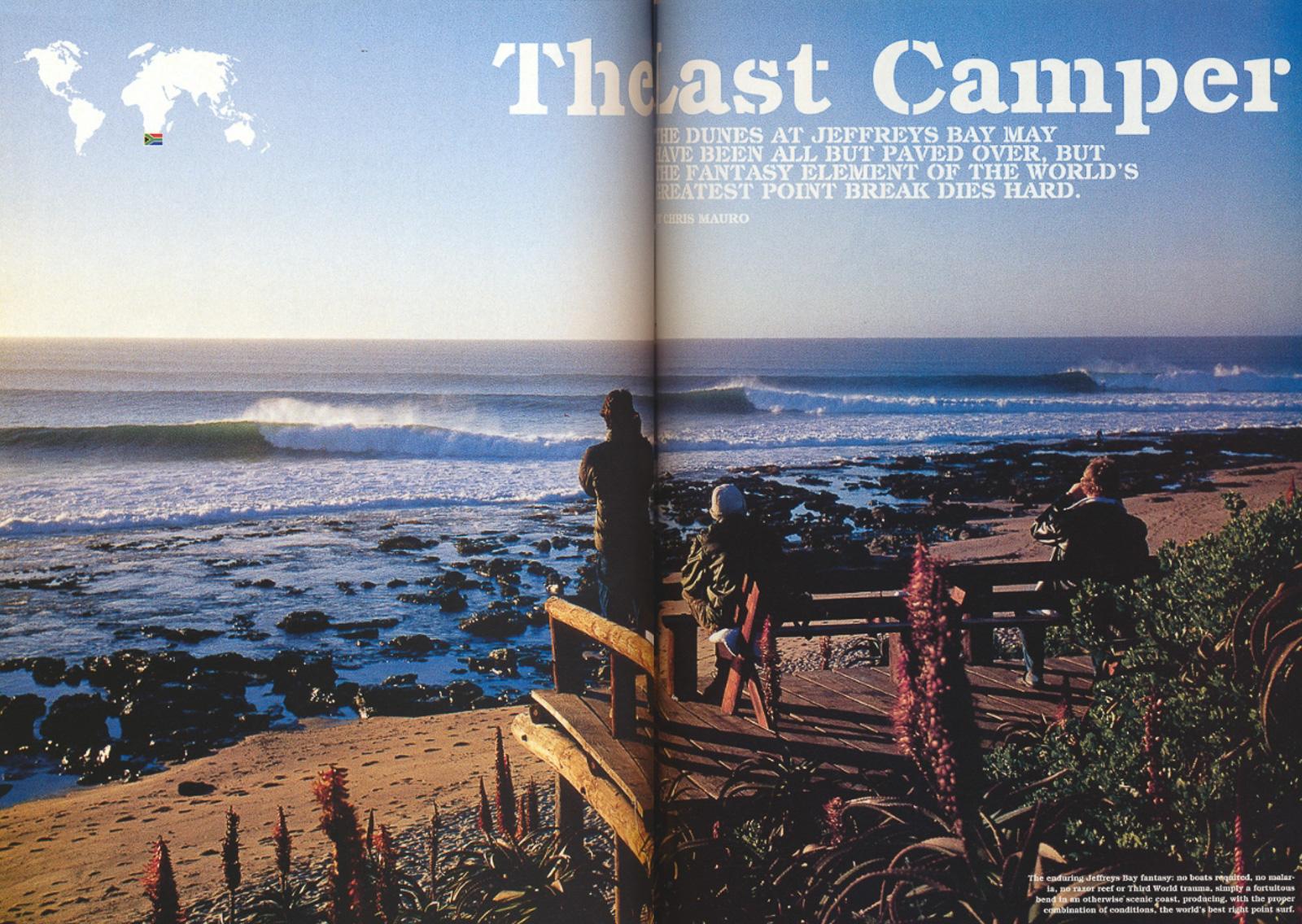

The moonrise over Jeffreys Bay throws a spotlight across the water as twilight fades. A steady flow of waves crash and peel down the point just below me, a stone’s throw away from where I sit in the bush. Overhead, clouds sail by, glowing in the white light. It’s a gorgeous, albeit chilly evening in this campsite, and bundled in my warm jacket I’m feeling a little awkward since both Doc, the frail old legend of Jeffreys Bay, and his young Xhosa friend, Gary, are struggling to find comfort in the cold.

“Gary, where are the matches?” The old man asks. “We’ve got to build a fire man, I’m fucking freezing.”

“Behind you, boss, by your pipe.”

“Ah, good." he says, relieved. “But Gary, I need you get some more wood for a nice fire tonight. We have a guest this evening. While you do that I’ll spark this bit up and prepare our smoke.”

“No problem, boss,” the young man replies. “I’ll get some good branches for us.”

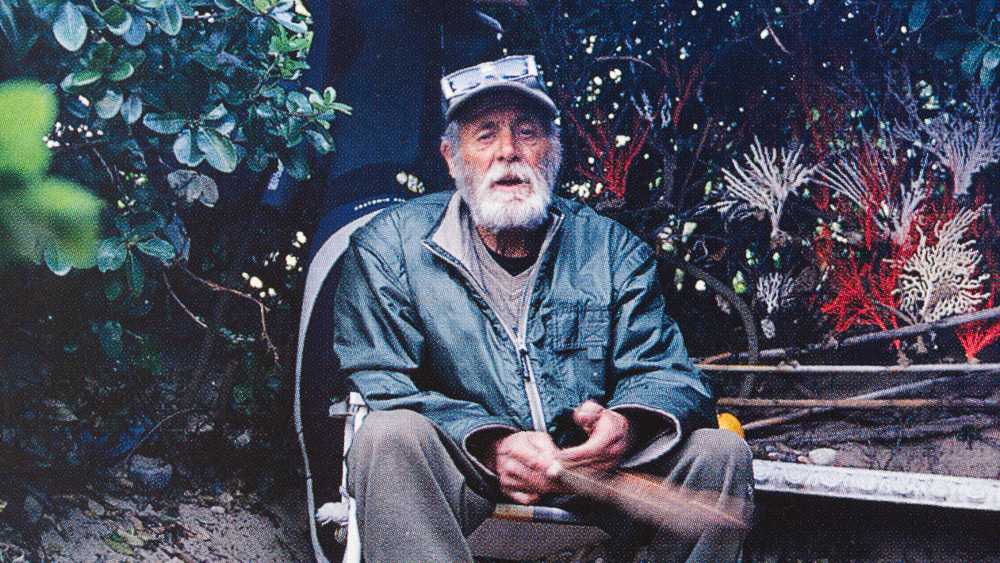

A few moments later we’re alone, and as he strikes a match I notice for the first time the deep creases on his face. Crouched over his tiny consignment of twigs he immediately begins talking story in his throaty voice. It’s merely a loud whisper really, and he’s constantly interrupted by extended bouts of coughing and hacking from lungs that are clearly wanting. Time hasn’t been kind to Tony van den Heuvel. His whiskers are gray, his skin leather and his body bent and fragile. Watching him turn his collar to the wind I can only wonder how many winters he has left. While the man in front of me could easily pass for 70 or even 75 years-of-age, he is in fact just 59.

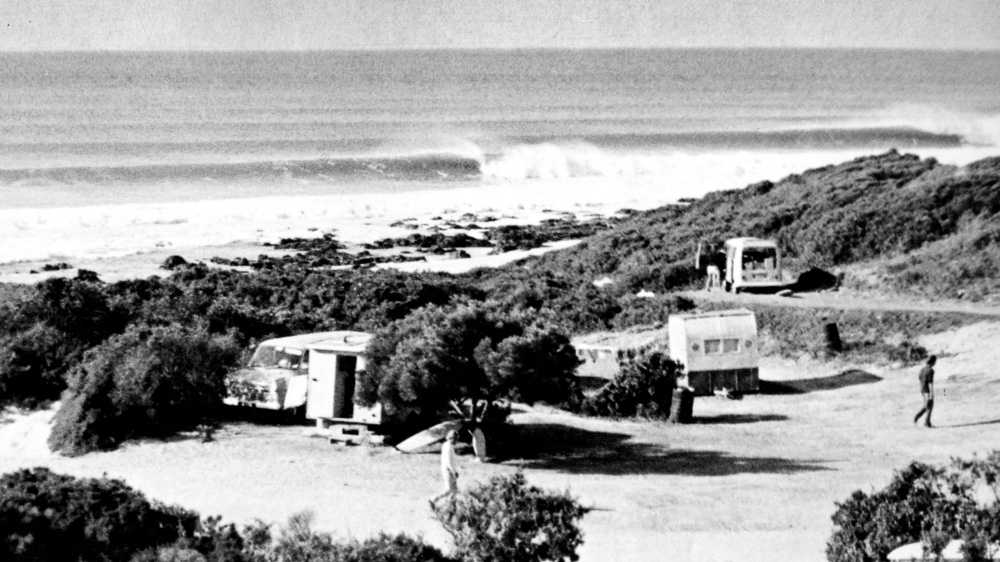

The two of us are inside a large fynbos bush atop the dunes overlooking Super Tubes, the best 100-yard stretch of reef at Jeffreys Bay. The clearing inside is about twelve feet long, and eight feet wide, with a tiny secret entrance that requires skilled yoga moves to pass through. It opens up on the inside, with a blue tarp serving as a retractable roof. This is Tony’s home, where he’s spent much of the past “35 years” he says proudly. “Actually, I’ve been in this site since 1997.”

I take in the surroundings.

“These dunes used to be littered with tents,” he explains. “But I’m the only camper left.”

Indeed he is.

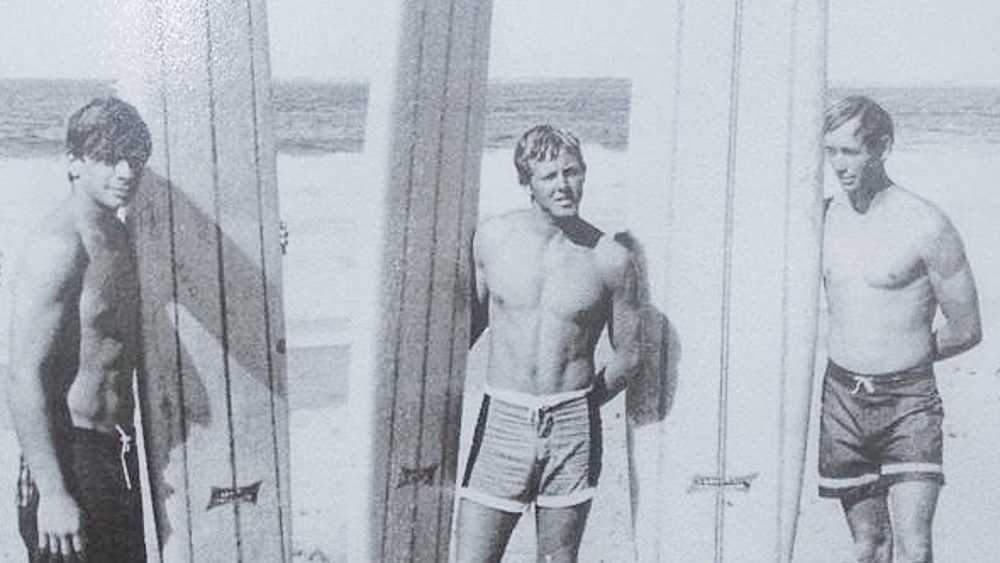

It’s quite remarkable when you realize Tony van den Heuvel, aka Doc, was also part of the first crew of surfers to arrive in Jeffreys Bay back in March of 1964. He was just 19-years old when Max Wetteland, Frenchy Fredrickson and Michael Peen invited him on a road trip to look for a place called Cape St. Francis. Americans Bruce Brown, Robert August and Mike Hynson had passed through their hometown of Durban four months earlier, still reeling over the wave they’d discovered in the south.

“They stayed for two weeks showing us how to surf the beachbreaks,” Doc remembers. “They were really hot.” But when the Endless Summer crew got the news that President Kennedy had been shot, they left the next day, distraught. Before the South African surfers could get detailed directions to St. Francis, the Americans were off to Kruger National Park to wrap up filming for their fledgling surf documentary.

Max Wetteland, a founding father of South African surfing, organized one of the first safaris south from Durban. He knew that with his surfing and fishing background young van den Heuvel would be a good traveling companion. Doc had scoured the coastline of Natal aboard fishing boats with his father and brother as a youngster; it served him well in the years that followed. Chasing sardines close to shore, Doc got the first glimpses of waves like Green Point, Belito Bay and Kelso, breaks he and his friends later surfed for the first time.

“I still remember coming south down the hill out of Port Elizabeth in the back seat of Max’s kombi,” Doc remembers. “It was a clear day, and when we rounded the corner you could see all three bays. I said to Max, ‘There! That’s St. Francis. That looks really good.’”

It was in fact the St. Francis Bay, but when they turned off N2 and headed for the coast a few minutes later they became the first surfers to ever encounter the actual wave at Jeffreys Bay. Standing atop the empty sand dunes they watched swells wrap into the northwest corner of the bay like spokes on a wheel, peeling one after the other down the 2-mile long point. Though they’d fallen short of their intended target of Cape St. Francis by about 20-miles, the crew knew they weren’t going anywhere

Jeffreys Bay would never be the same.

Like Columbus in the new world, the surfers who arrived in J-Bay altered its future almost immediately. The Dutch-descended Afrikaners who fished the bay and farmed the surrounding areas would soon have permanent guests, as would the indigenous Xhosa tribe. At the time of surfer arrival, interaction between the local Afrikaans and Xhosas was limited due to apartheid. Discussions between whites and blacks, or whites and coloreds (those of mixed race) revolved strictly around work related issues. The Xhosa, who resided in shanties on the southern border of town, provided most of the service labor in the tiny village that existed a few miles south of the point.

The surfers were a mere curiosity at first. On the surface they didn’t appear much different from the resident Afrikaans. Wetteland, van den Heuvel and company all sported crew cuts, as did most surfers in South Africa at the time. But surfers would be changing in the years to come, and young van den Heuvel would play a big part in that.

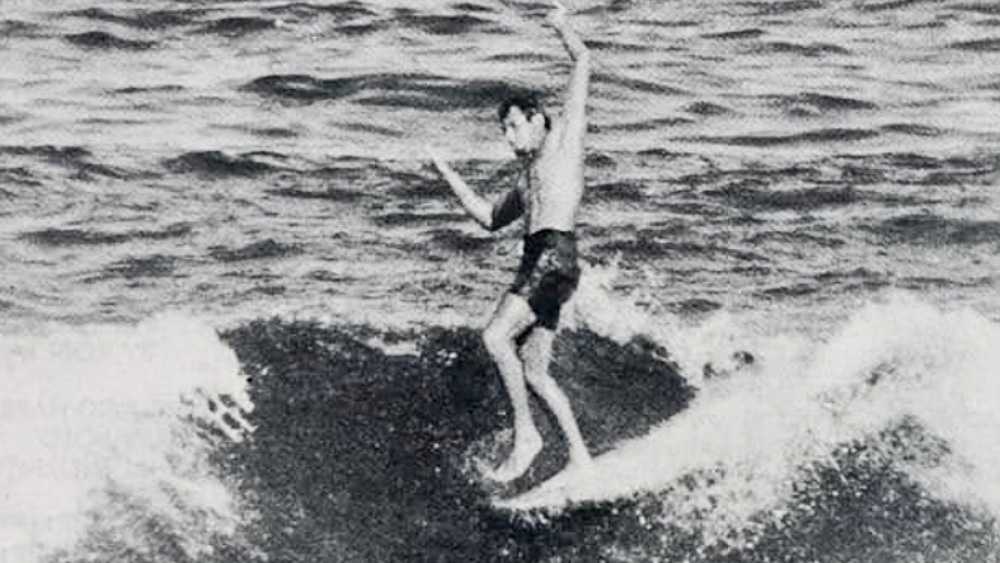

South African Mike Ginsberg lives in Hawaii today and works as an ASP judge, but back in 1965 he was a protege of van den Heuval. Five years his junior, Ginzy and his cohorts worshiped him. Doc had just won the South African Championships, and would go on to represent South Africa in international competition in Peru, Makaha and the World Contest in San Diego, where he stayed with the “enlightened” Skip Frye and fellow age-of-aquarian David Nuuhiwa.

“You must understand,” Ginzy explains. “In the '60s, we were all very clean-cut conservative kids in South Africa. So when we heard Tony was hanging out with Skip Frye and David Nuuhiwa we were terrified. We were getting reports that he was smoking pot and we couldn’t believe it. We freaked out."

Doc immersed himself in the hippy culture on his trip to California. He visited the Encinitas Hermitage, studied Swami Paramahansa Yogananda’s books, grew his hair long, and still managed to make the semi-finals of the world championship qualifier in Huntington Beach. But when he refused to cut his hair before the 1966 World Contest his conservative South African team manager kicked him off the squad.

“That was the end of my surfing career.” Doc says, remorsefully staring into his fire. “I’ve been here ever since.”

While Doc was away in 1967, the first published photographs of Jeffreys Bay ran in SURFER Magazine. At that time adventurous South African surfers like Ginzy were making the trip from Durban. When Ginzy and friends got word of Doc being jailed in California for overstaying his visa, they vowed to straighten him out upon his return.

“We planned an intervention right there at the airport,” Ginzy remembers. “Pot was not something we took lightly back then. We wanted him in rehab.” But the intervention didn’t go as planned. “He’d turned us all into potheads within three weeks,” Ginzy laughed.

By the early ‘70s, the sand dunes above J-Bay were littered with tents full of anti-establishment hippies from all over the world. Australians, Californians, and Brazilians set up camp alongside Doc, who had migrated south from Durban in 1968, months after his travels ended. It was during this time each section of the long wave was named: Albatross at the bottom, Point, Supers, and up at the very top a few brave souls began challenging the hollow racy sections at Supertubes and Boneyards. They lived off the ocean, catching fish, pulling oysters from tide pools and enjoying the nirvana that is Jeffreys Bay, but the ultra rightwing Afrikaners didn’t appreciate the new breed of surfers, with their long hair, lazy pot smoking ways, and especially their overt friendliness with the Xhosas.

“We’d just experienced this massive social change in America,” says photographer Jeff Divine, who first visited South Africa in the mid-1970s. “Basically, the black kids liked us because we had more in common with them. We’d share our music and talk about life when we could.” Black children lined the main road in the morning on their way to school and work. While their parents would offer a restrained smile and a low-key wave, the children would start dancing and waving in the street from a mile away at the very sight of a car with boards on top. Meanwhile, Afrikaner farmers grew increasingly intolerant of the surfers throughout the ‘70s and early ‘80s.

During apartheid white males were drafted into military service after high school. While many surfers ducked and weaved conscription, Afrikaners seemingly sprinted for the police academy or the army recruiting station. By all accounts, J-Bay farmers were essentially a bunch of tough-talking bootheads. Under mounting social pressure to change their racist ways they only cracked down harder on those they considered threats.

“It was almost like a police state,” recalls Divine. “They didn’t want us hanging with the blacks, and they were really harsh on weed.” Police brutality was frequent and heavy. Divine remembers one day when farmers, dressed in trench coats, blocked the road into town because they were looking for Doc. They found him and threw him in jail, where police hung him upside down by his ankles and tortured him. “They were famous for kicking your ass first and asking questions later,” says Divine.

Doc always understood their motivation. “I would usually get my weed in the colored areas,” he explains. “The police made it perfectly clear they didn’t want whites and blacks mixing.” But their actions never stopped him from visiting his fishing buddies who resided in the shantytown.

Relationships between the surfers and farmers might have continued to deteriorate if not for one fairly remarkable woman. In 1977, Cheron Kraak moved into town after separate yearlong stints on Reunion Island and Mauritius. Having lived on the coast since the age of 18, she fully understood the lure of Jeffreys Bay. In 1980, she opened the town’s first surf shop, Country Feeling.

Within a few years of her shop opening, Cheron was slowly convincing the Afrikaan city officials that surfing, and surfers, were viable assets to the local community. Her business thrived off surfing money, and she began employing more and more people, both black and white, as she added new stores. By 1984, the world’s best surfers and their fans were converging on J-Bay for the annual surf competition, the “Country Feeling Classic”. While proving surfers could pump money into the local economy she managed to push social justice as well, promoting several blacks to managerial positions in her store and ignoring silly laws that required separate eating areas and bathrooms.

But the ‘80s were still very tumultuous times in Jeffreys Bay. Local events mirrored the rest of the country’s troubles. As the population of J-Bay rose, so too did the two distinct spheres that people operated in: the above-ground world of the opulent whites and the seedy underworld of crime and murder that plagued the shantytown. When Jeffreys Bay experienced its own gold rush, everyone was affected.

“The calamari market exploded around 1984,” Doc recalls. “They called it the ‘white gold’.” Overnight, boats from Durban, Port Elizabeth and Capetown started showing up in Jeffreys Bay with their crews. On some mornings more than a hundred boats would take to the sea at once. Fishermen earned up to 1,500 rand a day (normally a good month’s salary) and factories were soon built in town. But with more and more Zulu boats from Durban arriving, tribal tensions exploded, a story as old as Africa itself.

Doc's young friend Gary, who still lives in the shanty, was a little kid at the time, but he remembers it well. “The Zulus are warriors,” he explains. “They bring violence to the town. The Xhosa boys were very restrained at first. We don't like the violence. But when they kept trying to take over we finally had to act.” One evening, a crew of Zulu deckhands started a fight with a group of Xhosas outside a bar. When the fight ended, one Zulu was dead and several more seriously injured. In the ensuing years more than 20 murders occurred in the relatively tiny town of Jeffreys Bay as the tribal violence escalated. But compared to tribal violence in Johannesburg and townships outside of Durban, J-Bay was a trip to Disneyland, and while the bodies were always counted, there were seldom screaming headlines.

Splitting his time between the growing surfing establishment and the mafia-run underworld of poachers and the poor, Doc was the surfer closest to it all. If the surf was bad he was fishing or scouting the rocks for oysters and octopus with colored friends like Gary. If it pumped he’d be racing the walls at Jeffreys alongside an ever-changing list of names: from Spreckels, Fitzgerald and Tomson to Carroll, Occhilupo, and Curren. Doc’s seen them all, even Slater, Parkinson and Fanning, and especially the new breed of J-Bay locals.

“I’ve seen a lot happen in this Bay.’’ He says through another coughing frenzy.

Looking around Doc’s camp I notice a leather holster filled with tools, a few woodcarvings dressed with acrylic paints, and hundreds of beautiful seashells. According to Doc there’s no point in having much more. His biggest luxury is the tiny battery operated sound system offering a faint background of jazz to this, another evening under the stars. I wonder for a moment if he’s taken the time to actually count them, but instead of asking for a number I inquire about his set of tools.

“Oh, I make shoes for a living,” he explains. “Ugg boots, sandals, moccasins.. .anything out of leather.” He buys the leather from tanneries and the farmers he made peace with long ago. The farmers can still hunt kudu and springbok around Jeffreys Bay. The fishermen still catch calamari. And thanks to the end of apartheid and Nelson Mandela, the first black President of the new Republic of South Africa, tribal harmony among Zulu and Xhosa has endured for the better part of a decade in Jeffreys Bay.

But rural life is rapidly being replaced with a cosmopolitan style. Fine restaurants, trendy cafes and sophisticated retail outlets have taken over the tiny markets that used to make up downtown. The line outside the bottle store can stretch around the block during tourist season in December, and hundreds of residents have converted their homes into massive B&Bs, as they play host to vacationing farmers in the summer, and the surfers in the winter.

Progress has obviously taken a toll. Today urban sprawl is choking the dunes that line the beach. Huge houses have replaced the tents on the beach and each year they pop up higher on the hillsides. Just a decade ago there was hardly need for a stop sign in town, but traffic is heavy now.

But while much has changed, the waves never have. This beautiful point remains a surfing Mecca, and surfing is the primary industry in town. Cheron Kraak, who now runs Billabong South Africa, is the town’s biggest employer. Billabong, Quiksilver and Rip Curl all have multiple retail outlets and factories in South Africa. Murals of the incredible waves adorn walls, billboards, coffee mugs and storefront logos.

But not everyone’s thrilled with the rapid economic progress. Some longtime surfing residents are saddened by the swelling crowds. Those longing to recapture the early magic have already left looking for new African horizons.

But not Doc.

Tony van den Heuval is the proud holdout of that wonderful bygone era. His marijuana habit still leads to occasional run-ins with authorities, but he’s widely viewed as a town treasure now. He refuses offers to sleep inside from friends and visitors alike, still preferring his camp—rain or shine. Beachside residents tolerate his use of their outdoor showers and he still runs to the petrol station when he has to go to the bathroom. It’s the life he's chosen.

With the evening winding down I cherish my final moments with Doc, and the miraculous era that will forever be gone someday soon. The fire has warmed him, he's had his smoke, and he’s retiring into his blankets where the sound of waves crashing will lull him to sleep.

“The waves will be good tomorrow,” he surmises.

“Should we check down the coast?” I ask.

“No, no.” He replies steadfastly. “This place has been very good to me, Chris—I’m not going anywhere.” With that Doc shuts his eyes and goes to sleep.

* * *

Note: Anthony van den Heuvel died, alone in his campsite, one month after Chris Mauro's visit.