SUNDAY JOINT, 1-12-2020: JOEY CABELL, ROBERT MITCHUM, MICKEY MUNOZ, KEONE DOWNING

Hey All,

At some point, as I tiptoe further into early adulthood, I will make a real effort to stop organizing my thoughts in the form of High Fidelity-style lists. Today is not that day.

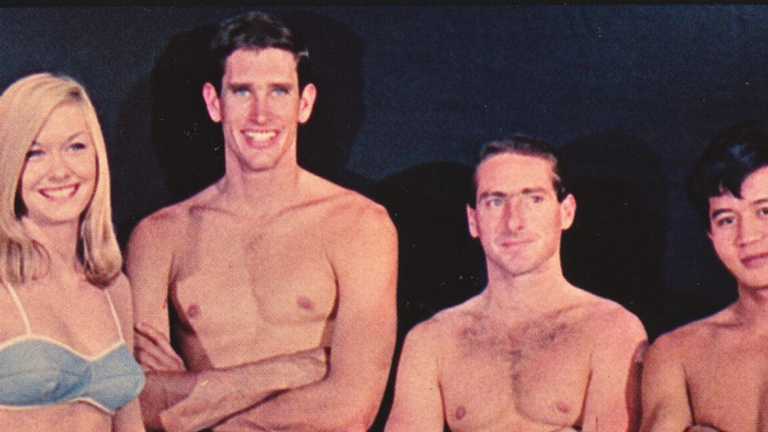

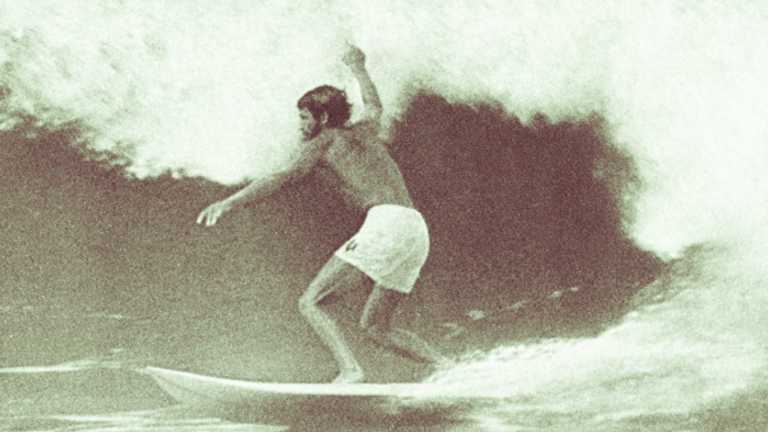

Today I announce that Joey Cabell is floating near the top of my Top 10 All-Time Coolest Surfers, and if you don’t share this opinion, then Robert Mitchum likely isn’t on your Top 10 All-Time Coolest Actors list, and now we have two problems. (My other nine cool-surfer choices, not in order: Curren, BK, Nuuhiwa, Rell Sunn, Bobby Brown, Bruce Irons, Matt Kivlin, Lopez, Rick Griffin.) Cabell’s coolness is multileveled. His surfing is chilled to the extreme, precise, calm, and beautiful, like a Greek statue come to life (watch here). His self-confidence is as quiet as it is towering and justified—every task, every project, Cabell does with an aim to perfection, and more often than not he hits the mark.

Coolest of all is the fact that Joey always follows his own completely unique path. In the past, he regularly quit surfing to work on other projects (cars, boats, skiing, the Chart House), and after one, two, three years away from the sport he would come back and ride better than he did when he left. Joey changes and evolves, but the cool is ever-present. It allowed him a singular place in surfing. Cabell was 31, with eye-wrinkles and the beard of Moses, when he finished #4 in the 1969 SURFER Poll—nearly everybody else in the Top 10 was in their late teens or early 20s. (It’s a topic for another Joint, but I think the sport, for all its youthful rebellion during the shortboard revolution, actually wanted a father figure. Surfing also ran a 1969 poll, and while Gary Propper’s called everybody else in his Top 10 list by their first name—David, Jock, Barry, etc.—he referred to Joey as “Mr. Cabell.”)

I wrote a profile on Cabell for Surfer’s Journal in 1996, and it’s one of those pieces that still rattles around in my head. It was a difficult task in some ways. Joey wasn’t an unwilling subject, by any means. He put me up for two nights at his beautiful new home in Honolulu (which of course he designed and built himself), and talked at length about his life and career, including his days as a beachboy gofer, his Duke win, and the creation of his mythical White Ghost surfboard.

But there was bad energy between Joey and his much younger wife, and the hours the three of us spent together (including a long Chart House dinner) were really uncomfortable, as she talked over Joey, and even eye-rolled him behind his back, as if she and I were sharing some private joke. It was awful. During an earlier conversation, when it was just the two of us, Cabell told me that relationships and family life were still a work in progress for him, and dinner proved it. The effort he was putting into this marriage (it was his second or third, I forget) was obvious. I have a vivid memory of her reminding Joey that they were going to the Van Halen concert the following night. A moment of awkward silence followed, then Joey tried to spin it in a positive direction, telling me how she was doing such a great job at getting him to experience new things. He was 57 at the time and looked miserable.

The other thing I remember about writing that piece was the interviews I did with other surfers, about Joey. The list included Mickey Muñoz, Nat Young, and Mike Doyle. Cabell was (still is) incredibly admired and respected, but everyone I talked with offered a variation of the same idea, which was that Cabell was, in essence, a man apart and that maybe he was somewhat cut off from himself, as he was cut off from others. Muñoz, as always, was amazing—honest, perceptive, funny, and warm, always warm, even when he put the blade in. “Joey is Mr. Perfect,” Mickey told me. “Except he could never keep his pecker in his pants.”

Muñoz was involved in the set piece of my Surfer’s Journal profile, which took place on Cabell’s racing catamaran during a 1978 run across the South Pacific. A squall came out of nowhere one night and the boat dismasted, knocking Muñoz out cold. Joey’s version of the story exclusively covered the steps taken to get Mickey comfortable (he was in pain, and very likely concussed, but recovered quickly), and to jury-rig enough sail to get them to the Big Island some two weeks later.

Mickey’s version of the story, on the other hand, was all about how, when forced for once in his life to slow down, Joey changed gears. He’d started the trip a man of abstinence, for example. But once they were slow-boating toward Hawaii, mast-free, with enough food and water to feel comfortable, Joey gladly drank the bottles of warm Hinano beer Mickey had stashed in his bulkhead and gratefully took his turn hitting the pinner joints Mickey rolled. “He discovered what it was like to live at a different pace,” Muñoz said. “We never talked about it, but I think it made a big impression on him.”

Thanks for reading, you guys, and see you next week.

Matt

PS: Almost forgot: here’s a clip I made last Monday of Keone Downing. Doing this got me thinking about George Downing, who was Cabell’s mentor, and that’s what led me down the tropical rabbit hole from which I have just this moment emerged.

[Photos: Bruce Brown, Jose Antonia de Lavalle, Rusty Miller, Art Brewer]