SUNDAY JOINT, 10-19-2025: TOM BLAKE'S SINGULAR ACHIEVEMENT

Hey All,

Unless he rises from his frosty Washburn, Wisconsin, resting place and rattles chains at me, this will be the last Encyclopedia of Surfing post on Tom Blake. I've always thought of EOS as an open-ended project, but given where I'm at age-wise (hale and 65 still means 65) and given where I'm headed work-wise (less EOS, more EOS Archive), when these Old Testament surf-world figures show up on the task list, the idea is to review their full collection of EOS pages, edit and amend, nip and tuck, and maybe, like today, say Aloha with a Sunday Joint.

I won't miss Tom Blake, to be honest.

I've said as much here and here, but I've come to realize that Blake mostly just confounds me, and while I still think his repuation is in many ways distorted and overblown, it is also true that I've probably failed to grasp in full what it is worthy and even great about him. In other words, it has been easier to fire away at Blake than to untangle how and why he became the beatified cofounder, along with Duke Kahanamoku, of modern surfing (SURFER put Blake at #2 on their 1999 "25 Most Influential Surfers of the Century" feature, saying, "Because Tom Blake was, we are"), so that is the job today.

First, here's where I originally parted ways with Blake and the silver-haired ranks of the Blake Navy. The Blake-designed hollow board was a rocketship for flat-water paddling but a tippy water-sucking handicap for actually riding waves. Blake was inducted earlier this year to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and while his Hall introduction notes that the new craft "influenced the future of board design" (paddleboards, yes, surfboards, no; the hollow was at best a developmental cul-de-sac), it also rightly points out that it was among "the earliest boards to be commercially produced" and made surfing "more accessible and popular." Blake himself called the hollow board "my new, perfected design," and claimed he'd restored the "vibration" of riding waves which the solid-wood board "kills entirely." Ad copy is not a sin, but let's pause here for a moment anyway. Blake's surf-directed innovation and creativity is the most attractive thing about him—the fin, the sailboard, improved surf photography, the idea that surfing itself is a study-worthy topic; all Blake inventions—and should be celebrated, and I feel nearly as pro-Blake in this regard as Sam George. But the hollow stuck around as long as it did because it was marketed like the latest model from General Motors, with Blake out front drum-banging the whole way. Back in Honolulu in 1945, after the war, Blake told a Honolulu paper that "we'll have a supply of [hollow] boards here soon—and at reasonable prices." This was seven years after John Kelly made the first hot curl. Young guns at Malibu and Windansea were already laughing at anyone who walked down the beach with a Blake-styled "kook box."

This is not entirely Blake's fault, really. But the acclaim for hollow boards should have been dialed back around the time Tommy Dorsey had 'em jitterbugging the Rendezvous Ballroom floor to splinters.

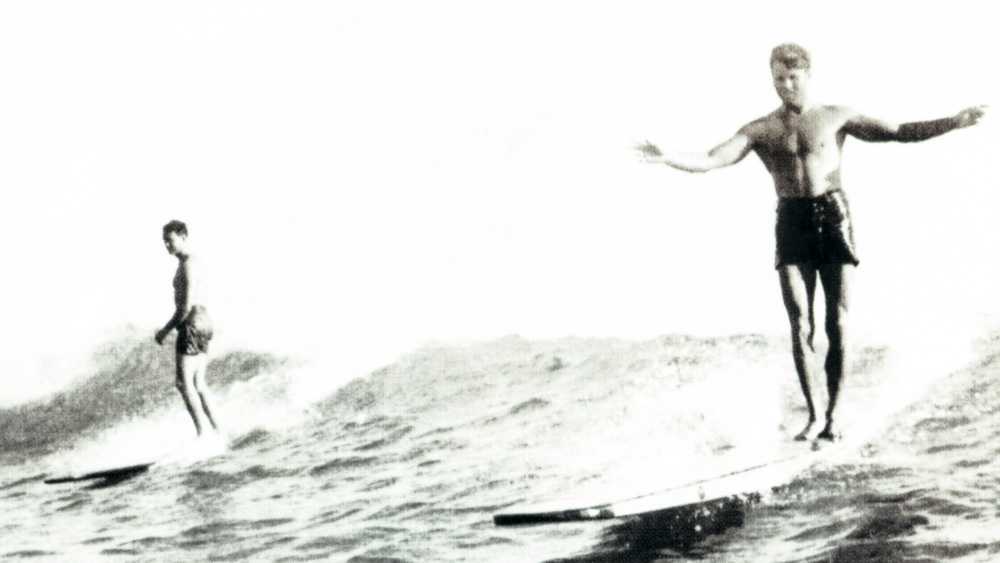

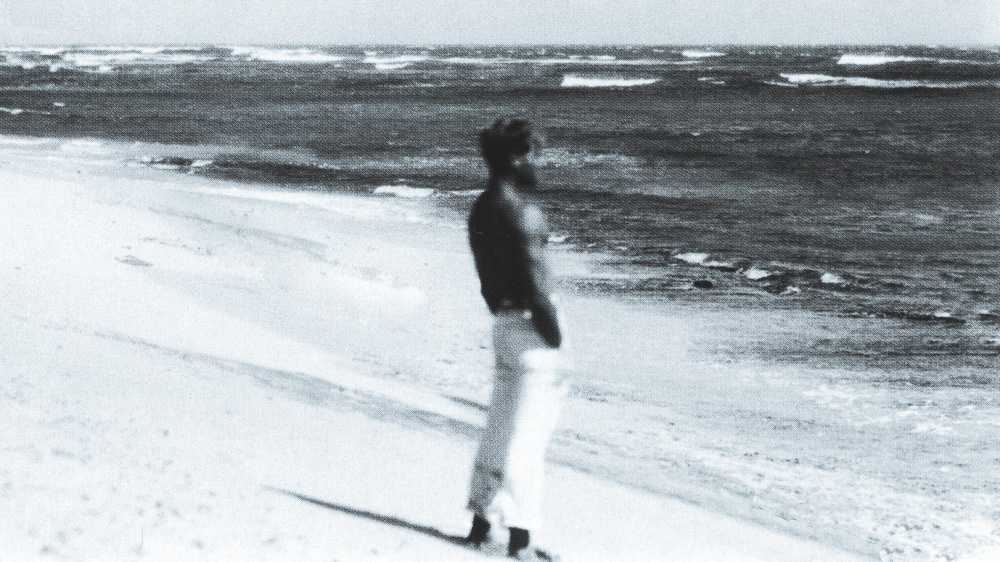

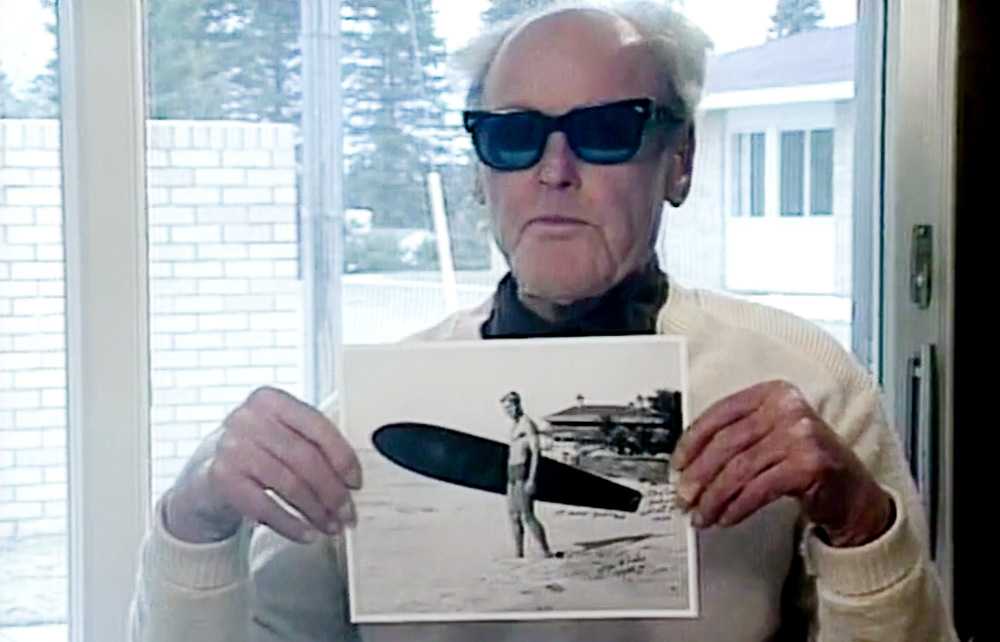

Two more things about Blake always jump out at me, and here again I have mixed feelings. The easier of the two is that Blake was surfing's first all-in peacock. The camera loved him, and Blake returned the favor with interest—he bought Duke Kahanamoku's barely-used Graflex in 1929 and kept it warm not just with incredible photos of the best Waikiki surfers but with a regular production of self-portraits. In fact, years earlier, while still in Los Angeles, before Blake even surfed regularly, he was setting up a camera and tripod on the beach, winding the self-timer, and striking dramatic poses with waves and rocks in the background. I want to eye-roll this so hard, but after putting a dozen of these shots into a mini-gallery (see here), I am floored not just by how good Blake himself looks, but how good surfing looks by association. To a point where I think that the Blake-produced display of surfing—the action shots and the self-portraits combined—may in fact be his ultimate contribution to the sport. The famous 1931 shot of Tom checking the waves at Black Point, shirtless, in white pants, hands in pockets, is as timeless and iconic a surf photo as you will ever find.

(There is another conversation to be had, but not today, about what it meant that Blake was surfing's first white star. A lot, probably. I have no proof but also have no doubt that there were 20 or more Hawaiians who, without notice from anybody except those in the water, rode circles around Blake at Queen's and Cunha Surf, and none of them—again, just guessing, but very confident—ever took a selfie. I'm not saying Blake himself used race to his advantage. But I think the white-owned press who put him on the front page and the white-owned companies who hired him to promote their boards for sure saw value in Blake looking like a wave-riding Clark Gable.)

One final loop back then we're in the homestretch.

Tom Blake was solitary and burdened and, as far as I can tell, humorless. But circumstances could not be more extenuating. No one in the sport, to my knowledge, had a rougher start. Blake's mother died from tuberculosis when Tom was 11 months old, and Blake himself then almost died from malnutrition. His father left Tom with relatives, remarried and started a new family, and had little to do with his first-born son. In high school, Blake had what he later described as a "tragic football experience" where he was kicked in the head, the Spanish Flu epidemic shut his high school down before Tom could graduate, and not long after that he "fell from social grace" and was "taken advantage of"—something he wouldn't talk about. Blake left Wisconsin and spent two years more or less hoboing around the country before landing in Los Angeles in 1921, where he quickly became a world-class swimmer, found surfing, and in 1924, age 22, rode his huge new enthusiasm to Hawaii.

This is where the best part of his life begins. The Tom Blake of legend exists almost exclusively on the beach and in the water at Waikiki, and to a lesser extent Los Angeles. Tom Blake: the Uncommon Journey of a Pioneer Waterman, a gorgous photo-heavy 2001 biography, gives a detailed look at all the highlights and is offered as a reverent large-format homage—but even here the essential Blakeian way of being is front and center. Chapter titles include "Lonely Beginnings," "Ever the Loner," and "Loner Endings." Blake himself, while in his 80s, looked back at and said, "Some people consider me antisocial. That's just the way life came for me. I found my greatest interest in swimming, surfing, and traveling around. It's a lonely life, that's true, but your friends are the trees and the animals, and the different people you meet briefly."

What did that mean in practice? At the end of this 1989 interview, Blake recalls his famous 1936 "mile-long ride." This is the closest he gets, at this stage of life anyway, to being animated. Heading up the beach after this incredible wave, with "line after line of surf" still pouring in, Blake walked past the Hui Nalu clubhouse—a massive hau tree next to the Moana Hotel—just as David Kahanamoku stepped foward to give Blake a one-man round of applause. "And that was the payoff," Blake says. "A real Hawaiian, acknowledging a haole [for] riding a wave." It is a gracious moment, the best moment on the video. But it also hides the fact that Blake, to the best of my knowledge, was never invited into the homes of the local surfers, many of whom had cold-shouldered him since the very public introduction of the hollow board, when Blake first used the new design to thrash the locals in paddle races of the late 1920s and early '30s, then flogged the hollow as a replacement for the "crude boards" used by the Hawaiians.

In other words, Blake got the wave of his life then walked home alone.

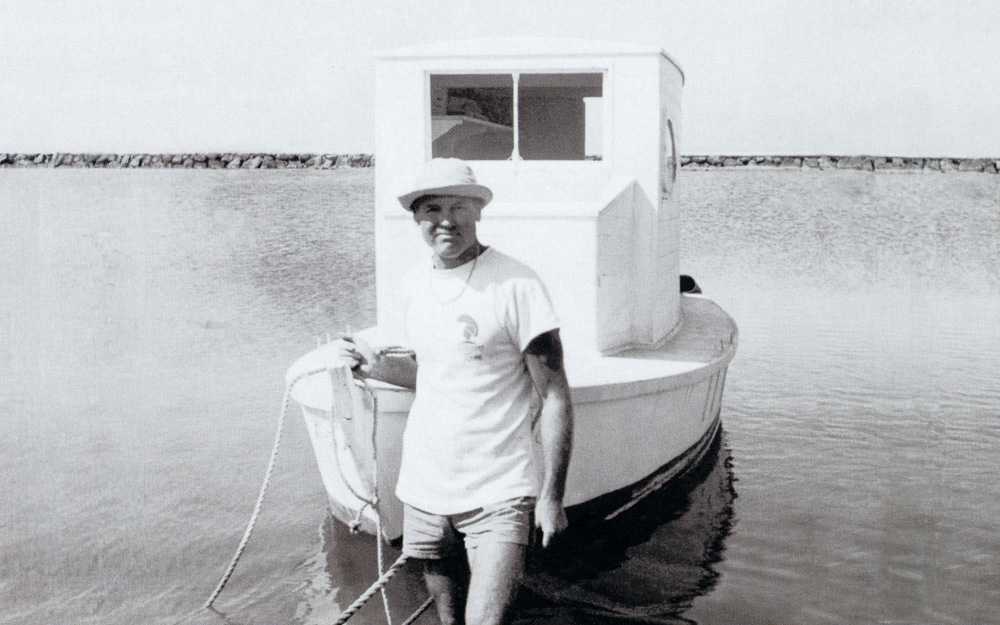

In the early 1950s, Blake lived alone on a doll-sized houseboat in Ala Wai yacht harbor. When he left Hawaii in 1955, he gave a maudlin interview to the Star-Bulletin. "I'm too old now, I guess. I'm no longer happy here." The 53-year-old was a quirky local figure by that time, the paper said. "He always walked around the city in knee-length khaki shorts, a coconut hat jammed on his sand-colored hair. Late in the evening he would seek his way back to his tiny boat, carrying a brown paper sack containing carrots, celery, a loaf of bread, some cheese, and ice cream for his lonely evening meal."

Blake roamed for nearly three decades, later quietly boasting that he'd set foot in all 50 states, and eventually, perhaps inevitably, went full circle and landed back in Wisconsin, not far from where he grew up. He'd been married once, in 1925, to an 18-year-old from a wealthy Hollywood family. The marriage ended after just a few weeks. Blake doesn't seem to have had any other serious romantic relationships. No children. Hundreds of admirers, many acquaintances, but no close friends.

In Wisconson, Blake lived on Social Security and a small VA pension in a two-bedroom senior living apartment on Lake Superior, where he walked each morning. But as noted in Uncommon Journey, "there was no one left in his hometown who remembered him." He died in 1994, at age 92.

My knee-jerk response is that Tom Blake in general is depressing to a point where I don't want to look at him for longer than necessary. Let's reshuffle our idols. Duke stays on top, but maybe we put Vicki Flaxman up there, holding a half-full bottle of Mateus Rose, with a crowd of Malibu friends. Or Dale Velzy, old or young, flush or busted, doesn't matter—Velzy always created, sought, and spread joy. I'll take the Velzy-embodied "Drink, Laugh, Surf" over Blake's famous reheated "Nature equals God" every time.

But again, I have to check myself. Humor and the company of others are the twin pillars of my own well-being, and maybe yours too, but that does not make for a universal way of being. Let's take Blake at his word. Swimming and surfing, trees and animals, got him through. Water restored him. I can blur my appreciation for surfing itself into a new and expanded appreciation for Blake. "Surfing will provide refuge to those in need," I wrote ten years ago. "Surfing will even, on occasion, open a path to eminence. You can count them by the dozen, starting with Simmons, Greenough, Dora, Morey, Peterson, Menczer, and Curren—Surfing Valhalla is filled with sublime misfits. Nothing about the sport should make us prouder."

Blake belongs at the top of that list.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.

Matt

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: color detail of Tom Blake surfing, from a 1949 issue of Esquire; detail from a 1935 Robert Mitchell Company ad; 1926 self-portrait on the beach at Santa Monica; Blake-style hollow boards in the UK in the 1950s; self-portrait from the mid-'40s; Blake surfing Waikiki in 1931. Surfing Waikiki in 1934. Blake on the beach, 1936. Paddling in California, 1930. Self-portrait on the beach at Black Point, 1931. Self-portrait with surfboards at the Outrigger Canoe Club, 1929. Blake and his houseboat, 1953. Blake at home in Wisconsin, 1989, holding a photo of himself from 1924. This Joint could not have been written without the photos and information gathered in Tom Blake: the Uncommon Journey of a Pioneer Waterman, by Gary Lynch and Malcolm Gault-Williams]