SUNDAY JOINT, 8-31-2025: CURT MASTALKA, SURF-MOVIE ROCKETEER

Hey All,

The Waikiki Shell, located just off the famous west-facing slope of Diamond Head, is a beautiful mid-sized performance venue; a smaller, more casual version of the Hollywood Bowl, with seating for 2,400 and a broad skirt of lawn for 6,000 more. Elvis played the Shell. Dylan, Sinatra, the New York Philharmonic, the Beach Boys, the Righteous Brothers, all played there. When your tour hit Hawaii, you could avoid the possiblity of a rainout and book the show indoors, at the nearby Honolulu International Center—but then you don't get the stars, the breeze, the night-air scent; you might as well be playing Milwaukeee. The Shell was and maybe still is the best place in town.

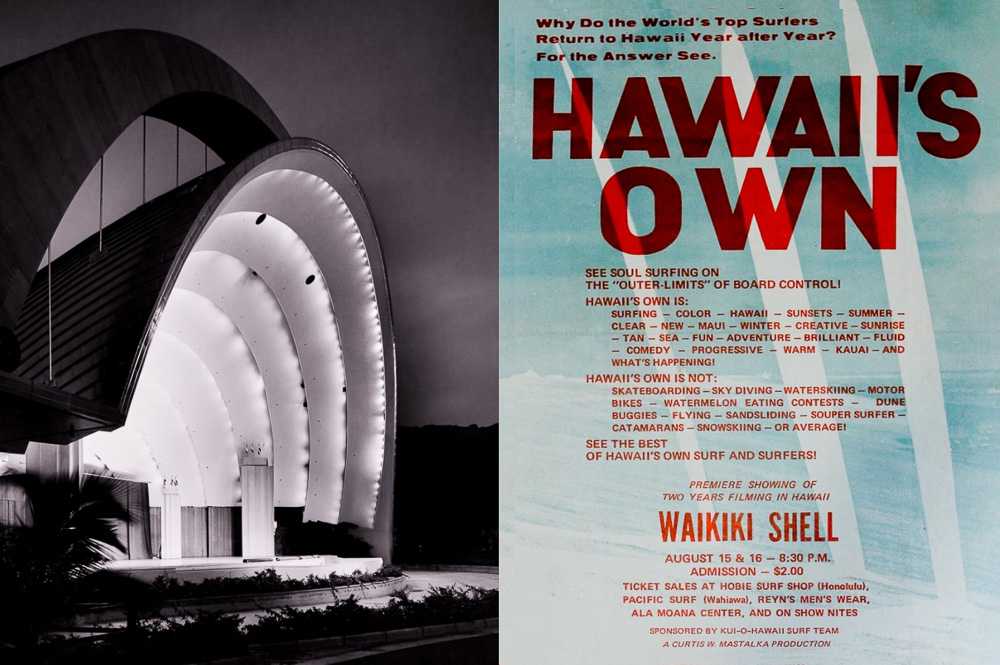

So it is understandable, I guess, that in 1967, a 28-year-old California-born surf-film novice named Curt Mastalka booked the Shell for two nights to debut Hawaii's Own, his first feature-length movie.

It didn't go well. Not a disaster, exactly. But projector issues on opening night pushed the start time from 8:00 to 10:00, the live narration was barely audible, and while 600 attendees on both nights was a decent pull, that still left three-quarters of the Shell seats empty. "It just isn't right for movies," a venue representative told the Star-Bulletin reporter who gamely reviewed the film, clearly puzzled as to why the Shell was chosen for no-budget surf movie debut in the first place.

But credit to Mastalka for taking the swing. And more credit for the fact that, over the next 15 years, he kept on swinging. Mastalka never grabbed the gold ring—or what passes for a gold ring in surf movie terms; big-wave rider and boardmaker Greg Noll had a side-hustle as surf filmmaker, and he later said he "could not think of a shittier way to earn a living." But how many people did? Endless Summer will always be the beaming Eye of Providence at the top of the surf movie pyramind, and just below that you've got Five Summer Stories, Morning of the Earth, Free Ride, Jack McCoy, then another stratum of 15 or so names and titles who round out the best-of lists, then a vast field of rank-and-filers, dabblers, grinders, and journeymen. My not-radical take is that Curt Mastalka floats somewhere above this bottom level but well below Brown, McCoy, etc.

Not for lack of trying, though, and let's jump ahead to 1971 and what might be called Mastalka's second debut, Seadreams, made in partnership with photographer Peter French. Seadreams opens with a long slow-motion watershot of 17-year-old Pipeline prodigy Rory Russell ninja-crouched inside the tube—but before he pops out we've cut to Rory in jeans and a tee-shirt, straw-blond hair in an uneven bowl cut, stepping barefoot with his pre-Lightning Bolt stick into a Piper Cherokee four-seater. Next thing we're gliding smoothly above the North Shore, with added lift from a sweeping orchestral score, looking down on a sunny fun-looking afternoon of overhead surf. Rory smiles, eyes glued to the lineup. He waves at the surfers below.

Nevermind that Russell lives beachfront on the North Shore, which means he drove to the airport, with board, then doubled back in a plane to fly over breaks located just up the street from his house. Forget also that halfway through the sequence we are suddenly and obviously in a different plane, on a different day, flying at a much higher altitude. Point is, Mastalka-French are striking a mood, looking for a new angle. Literally and figuratively trying to elevate the form. Except it doesn't really work. They've over-mellowed. Here's what John Severson did a year earlier with his Pacific Vibrations opening, for comparison. And MacGillivray-Freeman were just a few months away from unleashing Five Summer Stories with its thrumming psych-folk intro. You get one chance to make a first impression, as the saying goes, and with Seadreams, unlike Vibrations and Stories, our lapels remain very much ungrabbed. (You could alternatively make the case that Mastalka-French didn't lean hard enough into the mellow, the way Alby Falzon did with his mushroom-dipped Morning of the Earth opener.) The rest of Seadreams is fine, repetitive, greats bits here and there—synch up Barry Kanaiaupuni and Neil Young and I'm a pushover.

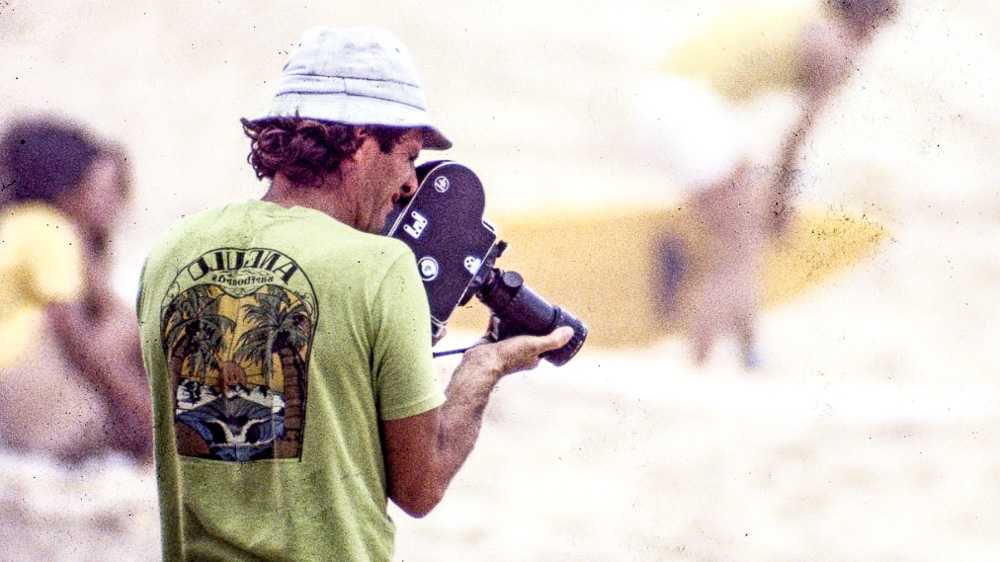

The Mastalka-French partnership didn't last, and 1973's Red Hot Blue finds Mastalka working on his own and putting heart and soul into his biggest, most ambitious idea—the Rocketmen. The concept was simple. Mount a 16mm camera to a motorcycle helmet, pass the helmet around to a willing group of hot surfers, let each guy strap in, paddle out, and roll film. Give us the direct eyeball-to-brain view of Pipeline and Haleiwa. George Greenough famously did more or less the same thing five years earlier, but not on the North Shore. Mastalka was right in wanting to level things up.

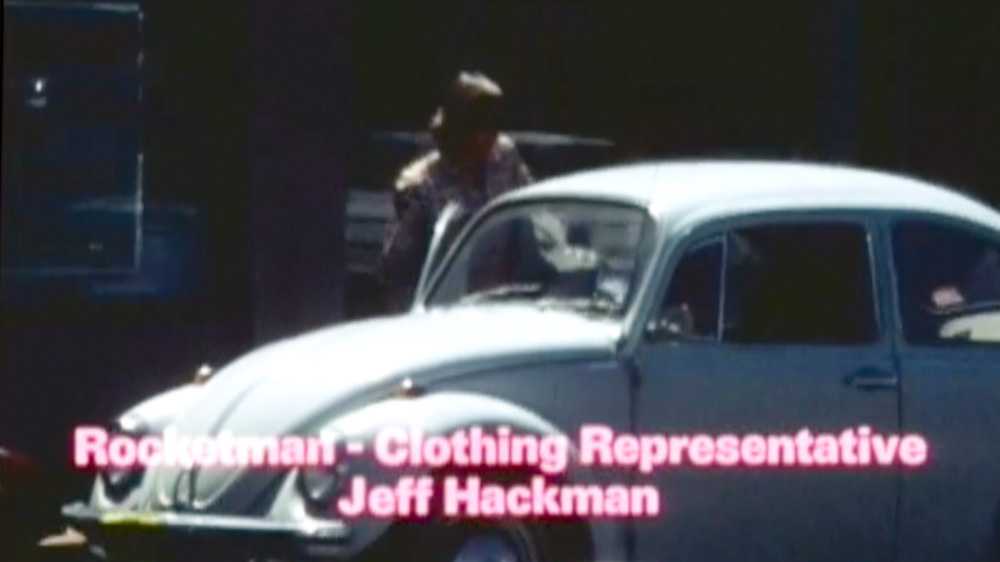

Judged on what Mastalka himself set out to do, the Rocketmen project was another well-intended fail. Or not fail, exactly, but the much-ballyhooed you-are-there footage is a big cut below the standard Greenough set at the end of the previous decade. On the other hand, the B-roll material Mastalka shows us before and in-between the helmet-cam shots—the filler, basically—is great, as we first meet the surfers on land, which in Jeff Hakman's case means watching him park a not-yet-rusting VW Bug just before making an in-shop call as a Golden Breed surfwear sales rep. This shot, plus the ones of the individual Rocketmen walking down the beach and paddling out with that monstreous 10-pound-plus safety-orange helmet rig—now my lapels are grabbed.

Read more about the Rocketmen project here. And a few years back I remixed the original and maybe too long (22-minute) Rocketman sequence down to a sleek two minutes, and you can watch that here.

1976's Sundance has Mastalka making his play for a general audience. A dozen or more post-Endless Summer filmmakers had already tried, but only Bruce Brown had pulled it it off. Surfing was trending all on its own in 1966, when Summer went mainstream, which gave Brown a huge advantage. But he was also of course a DIY savant filmmaker. Mastalka did not have the trend on his side, nor did he have the Brown touch. Here is the kid-surfer bit from Sundance, for example, and see if you can't think of six different ways Brown would have done this better, starting with not using minor-key circus music on the backing track. SURFER put a vaguely positive word-salady spin on their single-paragraph Sundance review: "It's a fast, clean, clear look at the various aspects of the Hawaiian oceanic experience. If you have a mate or a parent who's into surfing but hasn't been eating, living, and sleeping it for a decade or more, take 'em; it'll flash 'em out favorably."

Mastalka took a long break then returned for one last movie, 1983's Full Blast, in which he and Rory Russell reunite for an opening sequence that takes us inside the Wave Waikiki Nightclub and I won't sugarcoat it, nobody here, literally or figuratively, is putting their best foot forward—especially Rory, in full dancefloor gyration, 30 years old, in tight red pants and an expired Burt Reynolds moustache. Mastalka, 44, who told a reporter that year that "you have to be a masochist to make surf films" and that all his films thus far had lost money, promoted Full Blast as "The First New-Wave Surf Movie," even though New Wave was at that point as fresh and new as a Mork and Mindy rerun. The Star-Bulletin review for Full Blast was not kind. "It's like every other surf movie . . . geared to a specific audience. Sort of like pornography."

Blast works best when Mastalka reaches into the vault to give us a few rides from 1967's Hawaii's Own, and let's end there, because these shots are wonderful, beautifully filmed, and in my book Mastalka has earned our gratitude just by setting up at Honolua Bay on a small backlit afternoon, with teenaged Jock Sutherland out surfing and cutting up in a porkpie hat. The glide, the humor, the flair—much of what I hold dear about our sport is contained in this single Mastalka-captured wave you see below. Watch the whole ride here.

Thanks for reading, and see you next week!

Matt

PS: Sutherland kept the hat handy during this period. "One big day at Pipeline, probably in '67," Gerry Lopez later recalled, "a lot of the older crew kept trying to paddle out, and nobody was making it. The swell was really west, and everybody kept getting pounded back to the beach, all the way to Ehukai, then they'd get out and try again. All of a sudden here comes Jock walking down the beach with that palm-frond hat on. Throws his board into the water and paddled out without even getting his hair wet. Then as soon as he gets past the shorebreak, he sits up on his board, very casual, put his feet on the rails, looks back at us on the beach with a smile. Very subtle. Nobody else made it out."

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Leonard Bernstein at the Waikiki Shell in 1960; Honolua Bay, from Curt Mastalka's 1967 film Hawaii's Own; Rocketman Ricky Cassidy, in Red Hot Blue; detail from Seadreams handbill; kid surfer from Sundance; 1980s clubgoers at Wave Waikiki. Waikiki Shell and handbill from Hawaii's Own. Rory Russell in Seadreams. 17-year-old Rory Russell in Seadreams. Curt Mastalka with camera, photo by Gordinho. Rockeman Jeff Hakman, from Red Hot Blue. Hakman at work. Kid surfers from Sundance. Jock Sutherland and hat at Honolua Bay, 1966, from Hawaii's Own]