JOHN WHITMORE CROSSES THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE

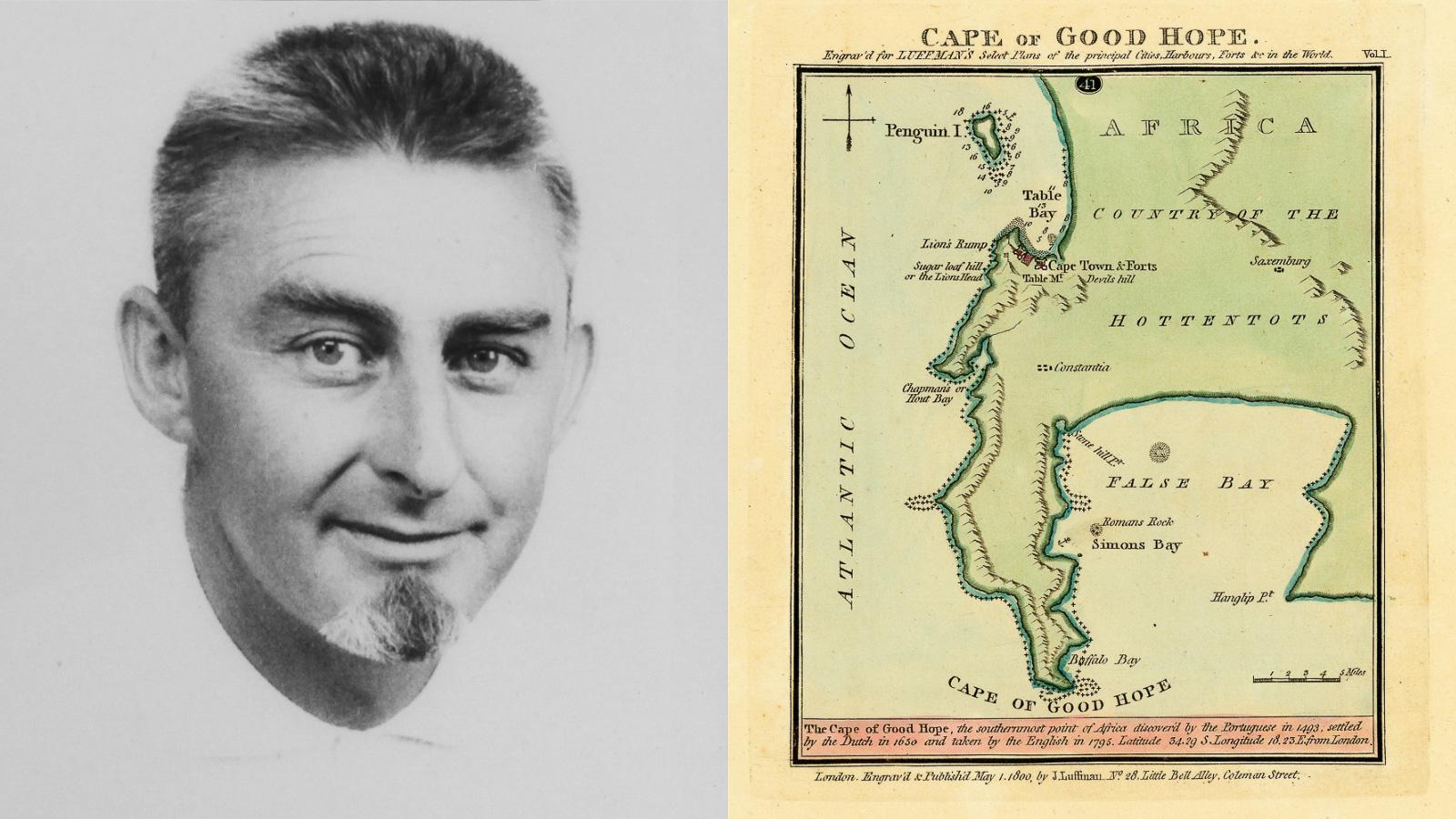

The Oom, Miles Masterson's biography on South African surfing pioneer John Whitmore ("Oom" means either "uncle" or, as in Whitmore's case, respected elder), was published in June 2025. The excerpt below picks up Whitmore story just as the a 27-year-old Cape Town VW salesman and surfing newcomer, married with two young daughters, began making EPS-foam surfboards out of a neighbor's garage for the small but growing number of surfers at nearby Glen Beach, some of whom had recently ventured into the bigger surf off the town of Kommetjie, on the south Cape Peninsula. The rest of the coast beckoned. Whitmore loaded up his VW bus and drove south.

* * *

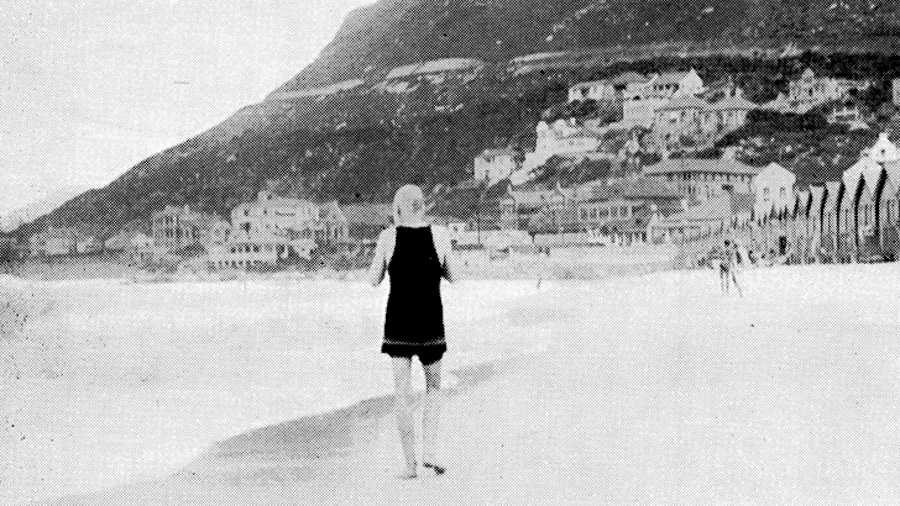

John’s next significant surf discovery was at Scarborough, a fishing hamlet 10 kilometers south of Kommetjie. Located just outside the Cape Point Nature Reserve, on the western side of the Cape Peninsula, Scarborough featured a few dozen wooden beachside shacks nestled among a canopy of Milkwood trees, surrounded by thick Cape fynbos. Fed by a small river, it was the perfect place to pitch a tent and surf all day. John identified a beachbreak and left-hand pointbreak at the end of a long, curved bay in front of a forbidding sandstone ledge, the takeoff area clogged by thick kelp. The waves at Scarborough were almost equal to the challenge of the Kom when the swell was up. Within a few months, the long rides and cartwheeling wipeouts of John and company attracted the attention of more willing participants.

Some were so intrigued by John’s surfboards that they tried to make their own. Keen to see the sport grow, he happily passed on his knowledge and helped them build boards as much as he could. The number of regular surfers in Cape Town swelled to more than a dozen. An annual Easter holiday weekend surfing gathering at Scarborough became popular for a time. After a surf, they warmed their frozen, Speedo-clad bodies in front of a driftwood bonfire, spiced up by a dram of brandy, muscadel or sherry. “Guys on the beach kept a continuous fire going,” described John. “No one minded about fires on the beach. They were stoked to see something happening.”

* * *

John’s reputation as the surfing pioneer and go-to boardmaker in Cape Town began to spread. His name slowly became synonymous with this intriguing new activity across the city. The exploits of the Atlantic surfers became regular fare in newspapers. Journalists often approached John for quotes and information on surfing. One of the first articles on the sport appeared in The Cape Argus in 1955, less than a year after John had first surfed at Glen Beach. A story entitled "He plans to make Kommetjie a new Waikiki for surf riders" described John as a “surfing enthusiast” who planned to form a “surf-boarding” club at Kommetjie. This location, the journalist wrote, “could become a second Waikiki or African Bondi Beach, according to Mr. John Whitmore.”

“Kommetjie, although the water is cold, is the most suitable of all the beaches in the Peninsula for this type of sport,” John told the reporter. “The waves come in over a shallow bank from a long way out. They are real Atlantic rollers. I hope to get enough people interested to form a surfing club. So far, there are only six regular surf riders at Kommetjie. Surfboard riding has been practiced in the South Sea Islands since before 1783 and has developed into a fine art. There is no reason why it should not develop into a major sport in South Africa.”

While he did not form a club at Kommetjie, John’s words would soon turn out to be prophetic. Yet it would not be a newspaper report on the sport that would truly expose surfing to the general population of Cape Town. A year later, the city’s main daily newspapers, The Cape Argus and The Cape Times, carried a thrilling lead story for several days: "Dramatic Rescue off Kommetjie."

On a sunny but windy Sunday morning in late October 1956, two German visitors launched a small canoe from the rocky shallows of the Kom basin, known as the "Inner Kom." The Teutonic tourists were oblivious to enormous waves at the back line, where eight-foot swells with wave faces up to 12 feet high thumped across the outside reefs. The Germans paddled through the pass toward the open sea, but a big closeout set wave mowed them down. John and the Camps Bay surfers watched the unfolding spectacle from the shore. Among them were his brother-in-law Earl Krause, Tim Paarman, and Brian Binedell, a young beginner surfer from Kommetjie, whom they usually phoned for a surf report.

“It was spring tide,” recalled Earl. “Not abnormally big, but occasionally breaking right across. We shouted to them, ‘Don’t go out!' They gestured, ‘No, no, don’t understand,’ and they eventually got in their kayak, quite a long boat – must have been about five meters. We were standing there and having lunch as they paddled out and it was just Murphy’s Law. They paddled fast, and saw this wave coming up, but instead of backing out, they paddled faster because they wanted to get over it, but they went straight into it. These guys had no life jackets so we waited a bit, because we thought, ‘No, these guys can swim.’ But they couldn’t. They were drowning.”

The Cape Argus reported the next day: “John Whitmore, who saw the incident, rushed into the sea with his board, followed by Brian, who had heard shouting on the beach. John reached the men first and took both of them on his board. Clinging to the men, who were weak from exhaustion, John was unable to make any headway with his board. Time and time again they were washed off by the pounding surf. By this time Brian reached John and he took one of the men onto his board. Skilfully maneuvering their boards, with their extra weight, John and Brian rode the foaming waves to the beach. They were taken to Mrs. Binedell’s house, where they were revived with food and hot coffee.”

John ended up with a few bruises when one of the Germans punched him in a panic, but all the rescuers and tourists emerged otherwise unscathed. The coverage hailed John and the others as heroes. The widely syndicated news story became enormously beneficial for the profile of the still mostly unknown sport of surfing. Thanks to the free publicity, as the city’s only surfboard manufacturer, John received a few more board orders. The rescue had alerted him to the advantages of incidental media exposure. It was a lesson he would put to good use in the near future.

John slowly began to realize that there was a market for his boards beyond the borders of his local beaches. Even more so when his group encountered a longstanding lifesaving and surfing community in the small seaside town of Muizenberg, in False Bay. John, Earl, Gordon, and company had occasionally surfed at Muizenberg in the mid-1950s during the colder months. They had rarely seen another soul in the water, so they were surprised to come across a group of surfers one winter’s day towards the end of the decade. They were even more amazed to find out that the sport had taken root here many years earlier.

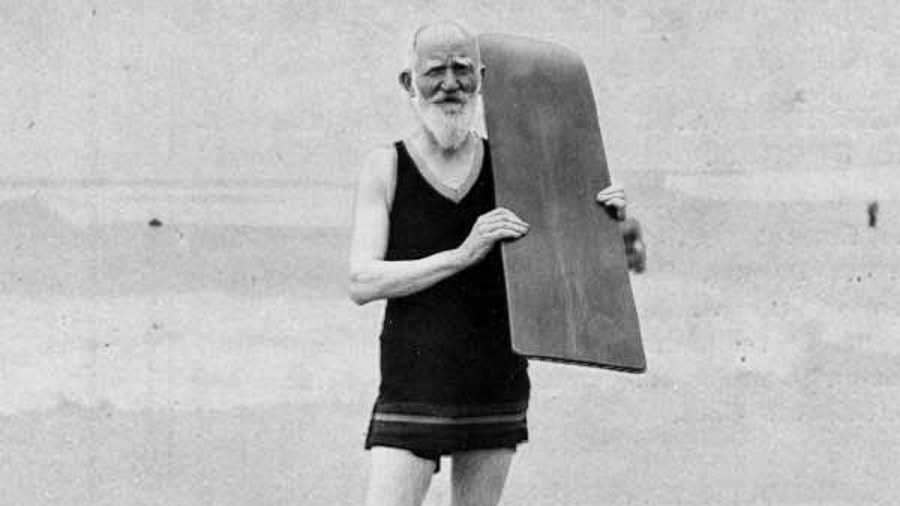

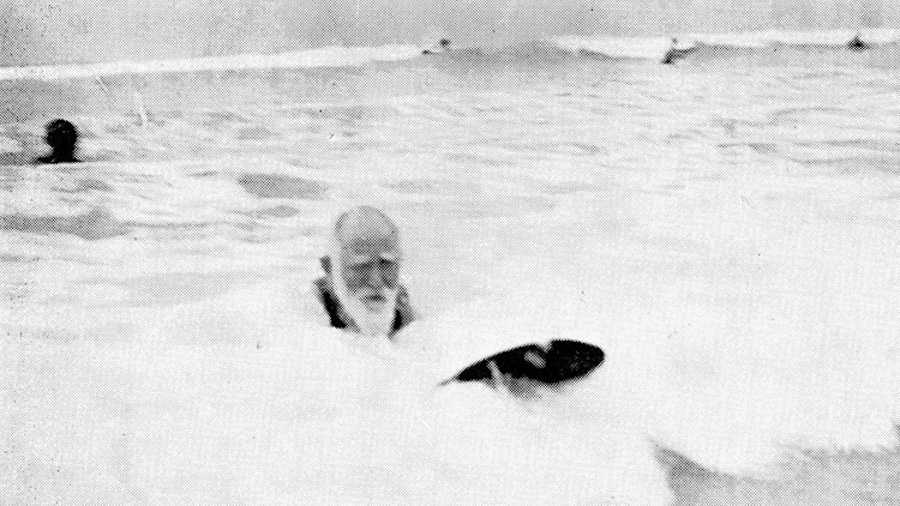

Situated at the foot of a small granite peak on the western shores of False Bay, 30 kilometers southeast of Camps Bay, Muizenberg features a long beachfront, lined with low-rise Edwardian, Victorian, and art deco apartment buildings. Many were bustling hotels at the time, as the town was one of South Africa’s most popular holiday resorts. John did not know it until then, but surf had been ridden at Muizenberg in different guises from the 1800s. Bodysurfers came first. Attracted to its warmer water and gentle, rolling waves, they were followed by wooden bellyboards at the turn of the century. This form of surf riding was popular with locals and visitors alike. Famously, Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw and British author Agatha Christie rode bellyboards in the breakers at Muizenberg.

Surfing appeared a few decades later, in 1919. Two American World War I marines – likely Californians on shore leave from a US Navy vessel docked in Cape Town – rode waves at Muizenberg standing upright on Tom Blake-style redwood and balsa boards. These mystery surfers are credited with introducing Hawaiian royal "he‘e nalu" (wave sliding) to Cape Town. Among the locals who gave it a go was one young woman, Heather Price, who is considered one of the first in South Africa to try the Pacific Sport of Kings. However, like most, her flirtation with surfing was brief. While bellyboarding remained popular, interest in the upright version of the sport disappeared once the Americans moved on, taking their craft with them.

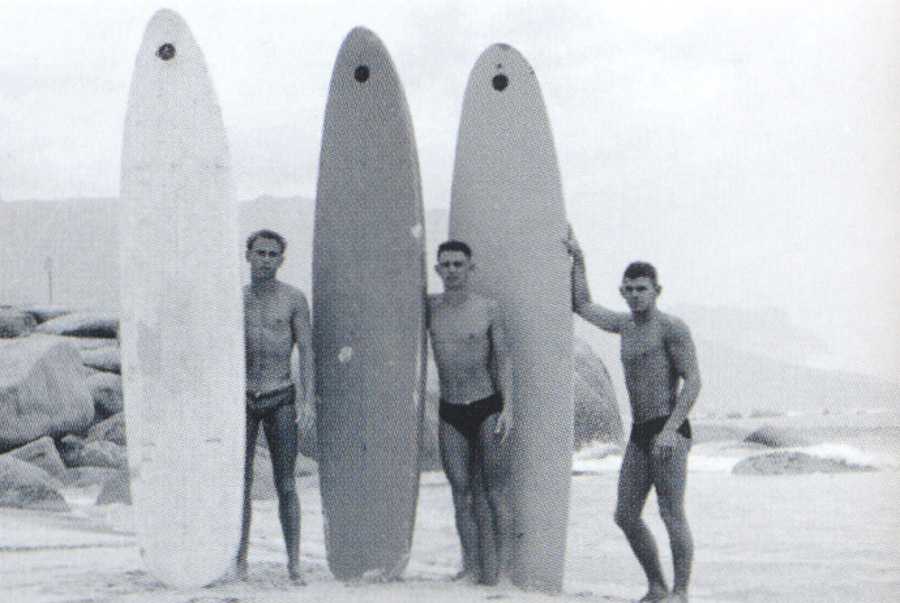

Stand-up surfing returned to Muizenberg a few years later, thanks to a South African WW1 pilot, Tony Bowman. In the early 1920s, Tony sent a letter to the Hawaii Tourist Bureau and was sent an envelope of photographs of surfers at Waikiki in Honolulu. Tony used these for reference to build his first surfboard. Joined by friends Lex Millar and Bobby Van Der Riet, he utilized timber framing, ceiling boards, canvas and house paint to construct his boards, which were built behind the Arcadia Tea House on the Muizenberg beachfront. Surfing declined at Muizenberg during the Great Depression and World War II, but recovered quickly after V-Day. The legacy of the "Arcadia Three," as well as hollow lifesaving boards obtained from Durban, inspired a handful of surfing devotees at Muizenberg in the 1950s.

Most of the Muizenberg surfers were lifesavers from the False Bay Surf Lifesaving Club (FBSLC), founded in 1959. They used homemade boards made of wood and canvas, likely assembled using the same magazine instructions as John. The False Bay locals were equally astonished to meet their counterparts from the Atlantic side of the peninsula. John’s polystyrene surfboards made their own seem archaic in comparison. Several placed orders for new boards from John. Some tried to convince the Cape Town surfers to sell them a secondhand Whitmore, while others attempted to make their own, again usually with John’s patient guidance.

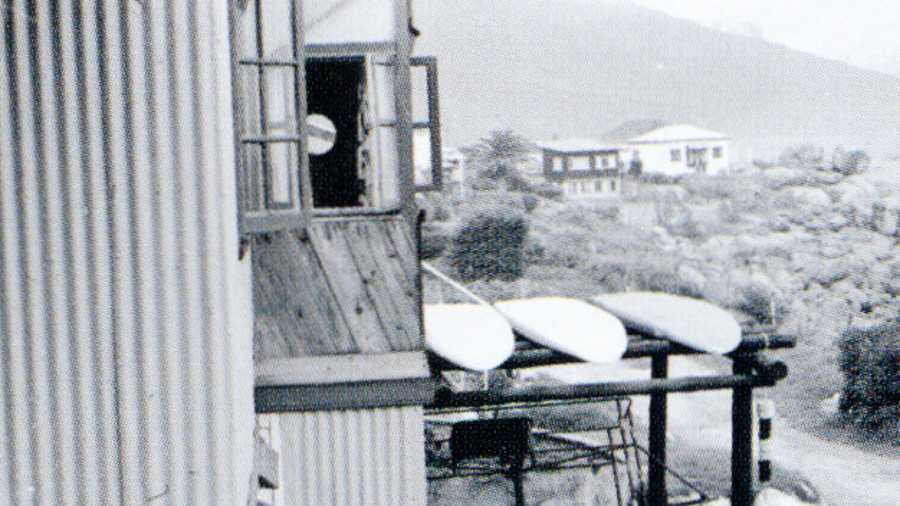

Scarborough regulars such as John Heath tried their hands at building a surfboard out of sheer necessity, which spread to the Muizenberg regulars. This was mainly because current owners rarely sold their boards, and John could not fulfill more than two orders at once, which meant a wait of up to a few months. Inevitably, the growing demand for surfboards outstripped supply. Broken boards also became as common as busted lips in a bare-knuckle boxing match. The Muizenberg surfers did not snap their boards in the mellower waves of False Bay, but the powerful surf breaks of the Atlantic exacted a heavy toll.

“A couple of guys from the FBSLC started making their own boards,” recalled Tim. “They used to come to the Kom. Scarborough can also get pretty big. The ‘okes’ (guys) called Scarborough ‘kak plank breeker’ (shit board breaker), because it would dump so hard.”

Thanks to frequent media coverage and word of mouth, John sold several more custom Whitmore surfboards the following summer to those who could afford one and were prepared to wait. Yet, though their numbers had grown, only a few Cape surfers regularly braved the powerful big wave spots around the peninsula. As more newcomers appeared, Muizenberg, with its gentle, user-friendly waves ideal for beginners, became the city’s most popular surf spot. This was especially true during winter when it was too wild and stormy on the western coast, but the surf was clean, warm and inviting on the eastern side.

* * *

A public car park at the southern end of Muizenberg, adjacent to the train station, became the mandatory meeting place for surfers at "The Berg." Many of the next wave of newcomers would hail from the city’s adjacent landlocked "Southern Suburbs" and learn the fundamentals of surfing here. This area became known as "Surfer’s Corner," which was easily reached from these suburbs by train, especially for those who lived near a railway station. Below an angled stone wall, swells bounced off the rocks and offered long, smooth rides to the beach. The surf occasionally washed up the wide concrete steps and sent plumes of salty spray onto the cars above. When the waves receded from the wall at high tide, the more experienced surfers such as John would jump on their boards from the steps and ride the backwash out to sea.

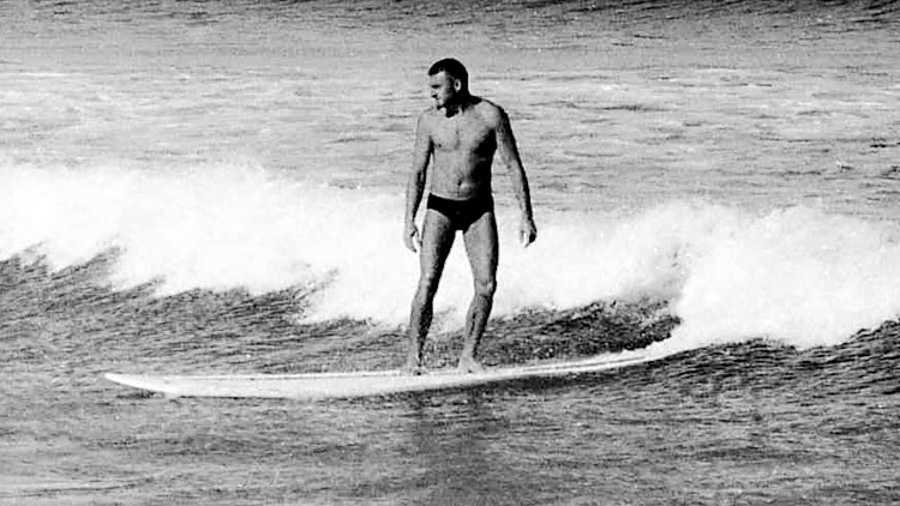

The nascent surf scene at Surfer’s Corner had a profound influence on an emerging cohort of new, younger Cape Town surfers. One was teenager Peter Basford, a supremely fit Navy diver, originally from Port Elizabeth, soon to become one of the most recognizable surf stars of the coming competitive era. Peter had heard of Whitmore Surfboards and John, but did not meet him until the winter of 1959. By then most of the Camps Bay surfers had come of age and bought their first cars from John. “They rolled into Muizenberg like a royal procession in their VW Beetles and Kombis,” recalled Peter. “John jumped on his board and paddled out with a cigar in his mouth.”

The Corner crew – mostly young kids from Muizenberg, Fish Hoek and the suburbs – only saw John and the Atlantic surfers in the colder months. Full of bravado, the Camps Bay surfers did not consider Muizenberg a place where "real" surfing was done, merely an opportunity to surf in warmer water as a winter storm passed. They believed they were the true Cape surfing vanguard and did not take the surfers from False Bay as seriously as they felt they deserved.

The Muizenberg surfers were adamant about proving them wrong. Whenever they shared the surf, they would do their best to outperform each other, which set the tone for enduring competition between the two groups. Yet, bonded by their love of surfing and the sea, most also became lifelong friends, especially with John, who was a supportive and amiable mentor they all looked up to, if not idolised.

Similar small cliques of surfers began to gather at most Cape Town beaches with rideable waves, from Big Bay and Blouberg in the north to Sea Point and Clifton on the Atlantic Seaboard, Fish Hoek in False Bay, and Kommetjie and Scarborough in the south. Every surfer in Cape Town aspired to own a Whitmore board, though many could not afford one. Glen Beach remained the surfing capital of the Atlantic Seaboard, though Muizenberg had usurped it as the most frequented break in the city.

While False Bay was fast becoming one of his main markets for surfboards, John’s focus as a surfer remained searching for big waves in the wildest parts of the Cape. Most weekends he and the Camps Bay surfers escaped the city to seek out virgin breaks and camp overnight, surrounded by untouched bushveld. They scoured every inch of the remote, deserted coastline, ever drawn by the lure of what new surfing treasure might lie around the next bend, or down some forgotten dirt track. John felt in his gut that there was a wave somewhere out there even better than Scarborough or the Kom, and he became determined to find it.