SUNDAY JOINT, 9-21-2025: JOHN WHITMORE'S SPRINGBOK FEVER

Hey All,

John Whitmore of South Africa came to the surf world's attention in stages between 1964 and 1968, as Endless Summer first played high school auditoriums in American beach towns, then leveled up to first-run theaters in New York, Paris, Tokyo, and London. Whitmore, 34 when Endless Summer was filmed, was the oldest surfer in the movie and his signature diamond-tipped goatee was already going gray on the flanks. With a few deft strokes, filmmaker Bruce Brown turned Whitmore into a memorable surfing character, and to this day he is remembered as the cheerful, boardmaking, VW-selling ringleader of a small but enthusiastic crew of Cape Town surfing originals. Everyone is having a good time.

Endless Summer's version of the man who would later be known as the "father of South African surfing" was a bit cartoony, and Brown clearly enjoyed poking fun at the Capetonians low-intermediate board-skills and penchant for traveling in a crowd. But Brown no doubt recognized a fellow mover and shaker—following the lead of Durban's Harry Bold, Whitmore was by that time also screening American-made surf movies and distributing SURFER Magazine—and for the next dozen-or-so years Whitmore stood at or near the center of nearly everything that happened in South African surfing.

The Oom, Miles Masterson's fantastically detailed 10-years-in-the-making biography on Whitmore, has just released, and I've been dipping in over the past two weeks. The book, unlike Endless Summer, regularly gives us a peek at the apartheid-charged politics of the era, and for me these are the most interesting parts. I was surprised to learn that Whitmore, for example, with connections to Frank Waring, a powerful National Party MP and Minister of Information, almost single-handedly managed to get a World Surfing Championships event held in South Africa. This was a two-part process. First, the country's seven-member team for the 1966 World Surfing Championships in San Diego were awarded "Springbok colors" and each received the pretigious green-and-gold blazer in recognition. "Waring and his department," Masterson writes of this event, "recognized that the tall, athletic and mostly blond-haired and blue-eyed South African surfing team were a great promotion for the country internationally." (Non-whites, by law, were ineligible to compete with whites, never mind qualify for Springbok colors, although on a case-by-case basis a few athletes—some South African, some from visiting nations, Eddie Aikau among them—were government-designated as "honorary whites.")

Two years later, in 1968, Whitmore convinced Waring to allow South Africa to host the next World Championships. Masterson quotes Durban's Sunday Tribune:

The government has given the green light for the holding of a 'mixed' world surfing championship in South Africa in 1970. The championships will be seen by 90 million American television viewers. Sixteen nations—including 'dark teams' from Hawaii and Puerto Rico—will take part.

In no way was this a sign that the apartheid-formalizing National Party government was softening its position on race. At ground level, by law and with relentless police and judicial enforcement, blacks were kept separate from whites, and whites held all political, legal, and economic power. No exceptions. The tiny South African Surfriders' Association, cofounded by Whitmore in 1965, was as white as the National Assembly. (Whitmore, like everybody in the country's small but beleaguered realm of global-connected athletics, had a dozen different ways of saying "Sports and politics don't mix," and that he and the team were "Just here to compete.") At the international level, however, other nations had begun turning the screws on South Africa with sanctions and boycotts, and by 1968 the Pretoria higher-ups felt it might be a good idea, public-relations-wise, to allow "mixed" events with "dark teams" included.

Too late. ABC-TV announced in 1969 that it would not cover the World Surfing Championships if the contest took place in South Africa, and that was that. The 1970 event was quickly given to Australia.

1972, same thing, Whitmore pulling every possible string to get the World Championships booked, only to have ABC again say they would not cover the contest. This time it went to San Diego. That more or less was it for Whitmore and organized surfing, as the following year he resigned from his long-held South African Surfing Association presidency and became Africa's sole licensee and builder for the Hobie Cat sailboat. In 1979, Whitmore at last got his wish, as the Hobie 14 World Championships took place at Plettenberg Bay, between Durban and Cape Town. Whitmore himself handed out the trophies.

The Oom presents John Whitmore as bright and ambitious, at times overbearing and prickly, but good-humored and absolutely dedicated to the development of surfing in South Africa. He was a man of his times, as the old cliche goes, and Whitmore's time was more or less 1963. By the time the Endless Summer crew rolled into Cape Town, Whitmore, with his GI haircut and penchant for cigars, was already an establishment figure within the sport: in 1963 he described "the younger generation" of surfers as being "precocious, loud-mouthed litterbugs," and a few years later he was dead set against the idea of surfers becoming professional because he believed that leaving the amateur ranks would steer credit away from South Africa itself.

Whitmore was also unfailingly generous with his time and knowledge, mentored a generation of Cape surfers, and was enthralled not just by wave-riding but the beach and ocean in general—he turned other people onto surfing and ocean sports because it was his business and career, yes, but also out of a genuine belief that the joy should be shared, and that others would find all of these seafaring activities as beautiful and exhilarating as he did.

Masterson describes Whitmore as "a patriotic, sports-mad South African," and much of The Oom illustrates the point, for better and worse. The book is at its best when detailing how Whitmore's ambitions ran against and braided into the politics of the time. But Whitmore himself is at his best, for me anyway, in the early chapters, when he's in the family carport making surfboards from wood and canvas, then driving up the coast, headland to headland, bumping over empty dirt roads, looking for a new wave to ride.

Thanks for reading and see you next week.

Matt

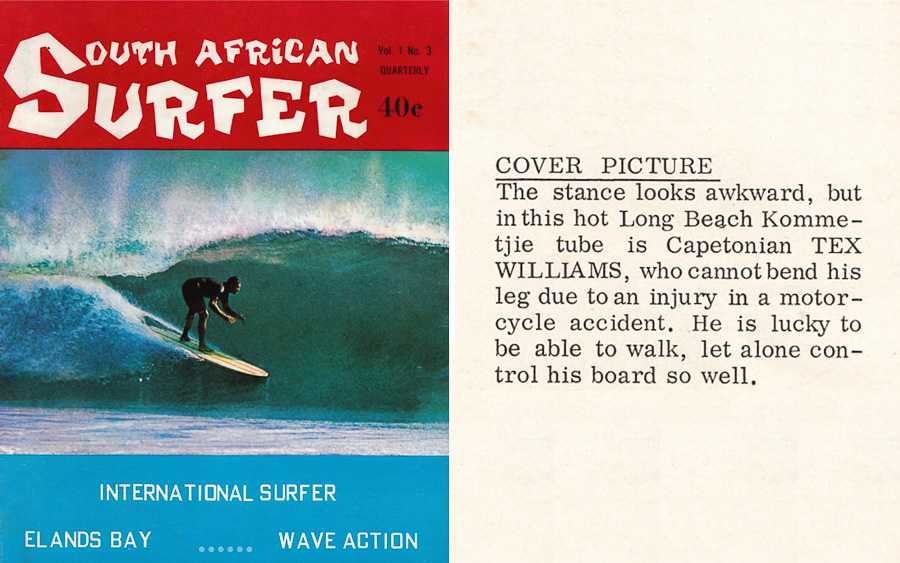

PS: Whitmore's 1965 article on finding a sublime left pointbreak at Elands Bay ran in the third issue of South African Surfer, the cover of which is eye-catching to say the least. It gets even better when you read the caption: "The stance looks awkward, but in this hot Long Beach Kommetjie tube is Capetonian Tex Williams, who cannot bend his leg due to an injury in a motorcycle accident. He is lucky to be able to walk, let along control his board so well." Cape Town surfers were tough as shark skin.

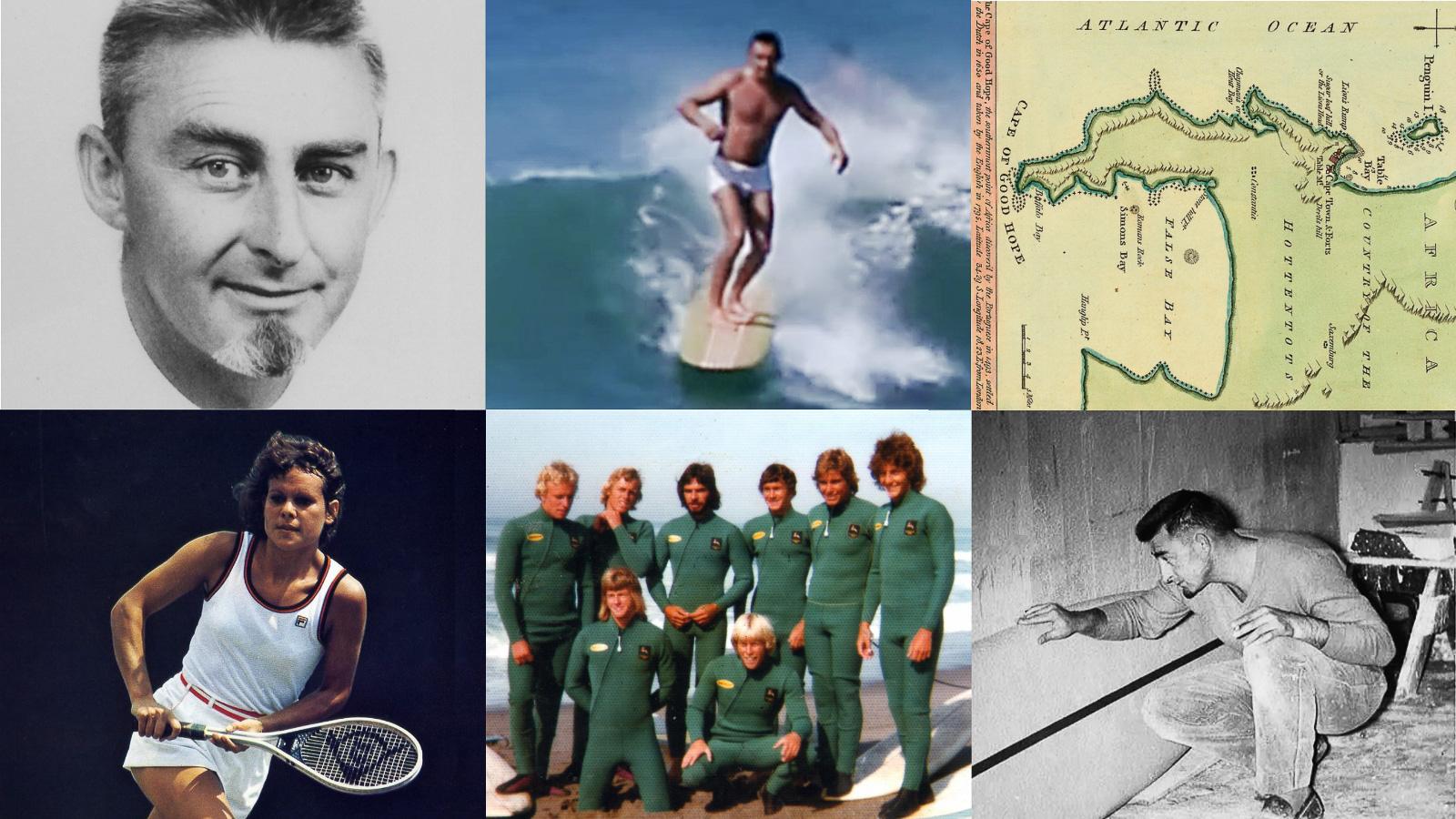

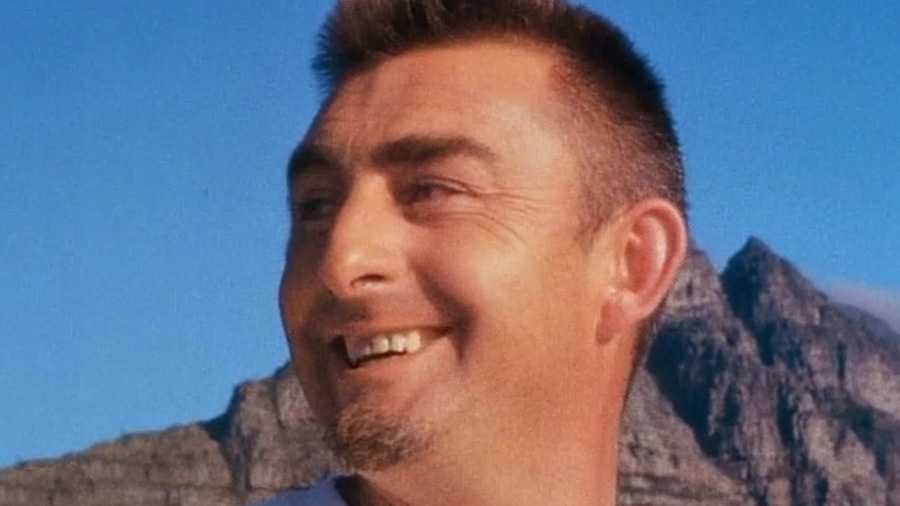

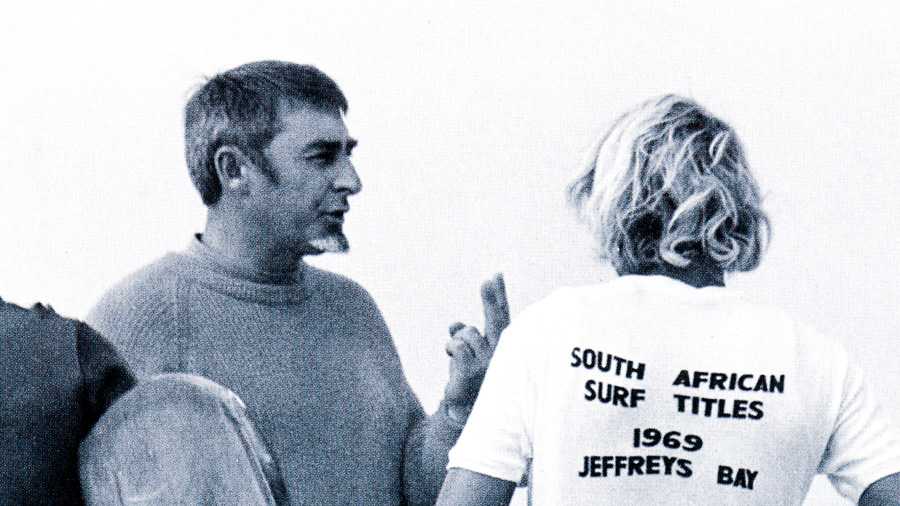

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: John Whitmore around 1965; Whitmore surfing in Endless Summer; detail from antique map of Cape Town and Cape of Good Hope; Whitmore inspecting board, early 1960s; 1975 Springbok surf team; Australian Aboriginal and "honorary white" tennis player Evonne Goolagong, early 1970s. Scenes from Endless Summer's Cape Town sequence, filmed in 1963. Beach sign in Cape Province, 1974. Whitmore at the 1969 South African Surfing Championships. Whitmore, third from left, with the 1966 Springbok team, leaving for the World Championships in San Diego. 1965 issue of South African Surfer magazine.]