SUNDAY JOINT, 8-10-2025: FLUID FRED'S FREUDIAN FLAREUP

Hey All,

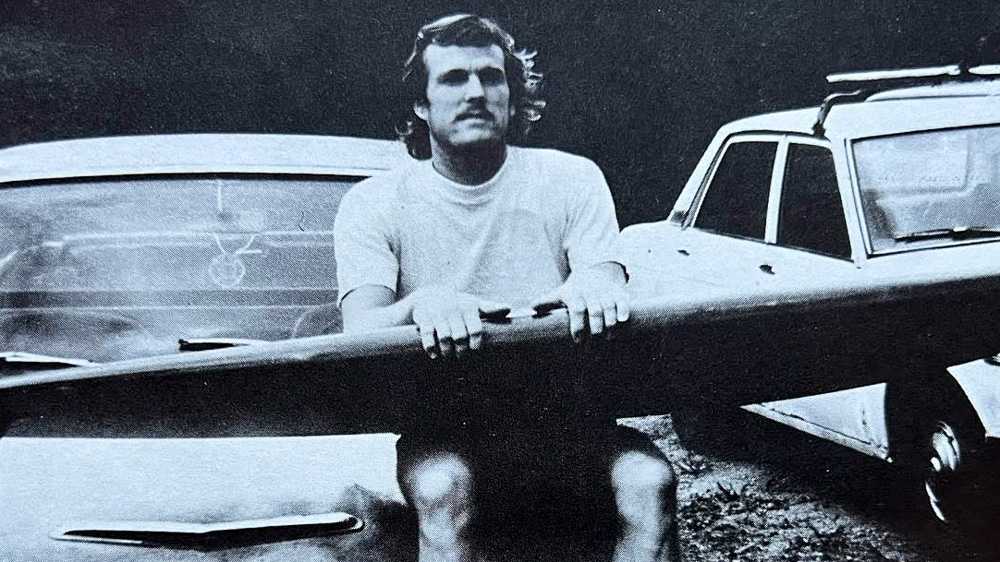

Three-quarters of all North Shore WCT winners between 1975 and 1980, men and women, rode Tom Parrish-shaped boards, and that might be lowballing it. Parrish was of course the apex craftsman at Lightning Bolt—"The Man with the Red-Hot Planer." He was also a friendly, upbeat, one-man corrective to all that wizardy shaper-guru hoodoo we got stuck with in the '60s and '70s. If you somehow managed to book an in-person custom job with Tom, it not only meant you'd soon be taking delivery on the cleanest, fastest, most forgiving 7'6" roundpin gun in the surfing cosmos, but the handsome foam-speckled man who brought it forth would shake your hand, smile, hear you out, exchange ideas.

Tom and I have emailed occasionally over the past five or so years, and because he is both eloquent and knowledgeable, in addition to everything I've just said, he has by a longshot become my favorite and most-trusted surf contest naysayer. Yes, the gleam on Parrish's career is partly due to the fact that his boards put hundreds of trophies on beach-town mantles from Cocoa Beach to Haleiwa to Sydney—but Tom himself long ago came to regard surfing competition as a distraction at best, a poison at worst.

So there was a tiny little Tom Parrish figure standing on my shoulder, tsk-tsking and shaking his head as I wrote the last two Joints (read here and here), both of them contest related. No email from Tom after the first Joint. But the next one, where I described "three things to appreciate and value about contests in general," was too much, and the email arrived just an hour or two later, with Tom saying my list was "like naming three good things about driving the LA freeway system."

Keen as ever. Yet I am inspired nonetheless to add item #4 to my list, and Tom, we can discuss the other three but this one is rock-solid. Contests are good for women's surfing.

To be clear. Surfing has done a terrible job at platforming women, especially in decades past. But without contests the women would have been practically invisible. I'm hot on this topic because last week I finally got my hands on a John Bennett film titled Blue Cool, which has a short segment featuring the women competitors in the 1970 World Championships. And again, no awards to anybody in surf media for how one-sided the coverage was on this particular event. Entire long-form articles were published where the women's results are barely and grudgingly mentioned. But now we at least have a visual on how Sharron Weber surfed her way to her first world title, and we get a brief look, the only one I've yet found, of two-time champ Joyce Hoffman ('65 and '66) on a shortboard. We also see defending world champion Margo Godfrey, still just 17 years old, runner-up to Weber in 1970 but (no disrespect to Sharron) the runaway best female surfer of 1970. I cannot say this enough. Margo was a surfing savant. Tom Parrish will tell me it doesn't matter, and maybe he's right, but had the WCT launched in 1968, and had Margo been inclined to compete year after year, she would be the sport's all-time world title leader, a crown or two ahead of Kelly Slater.

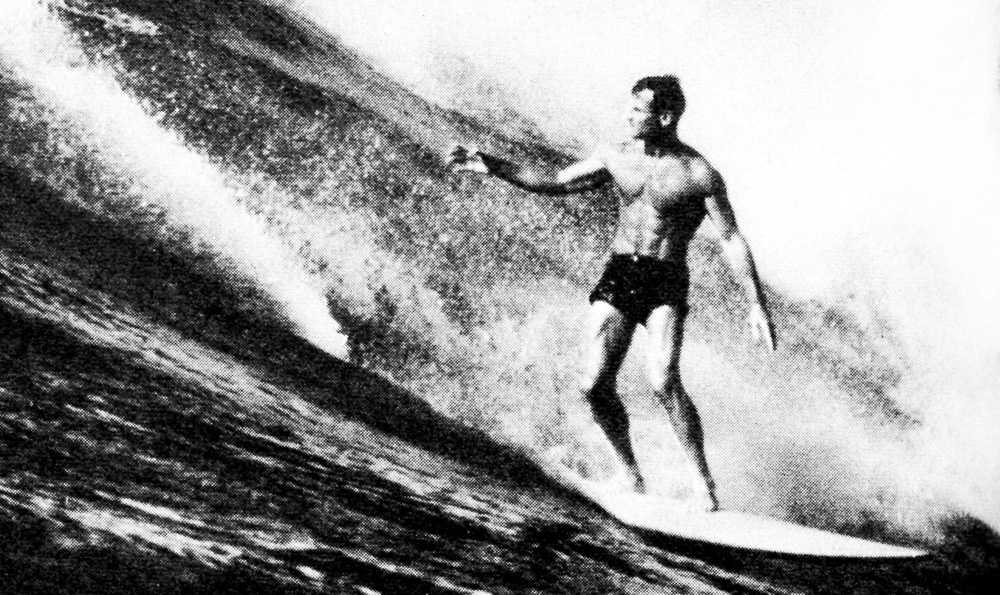

What does Parrish suggest we focus on, instead of contests? "Style. Individuals who surf with individual style—which surf contests destroy. Style is a more interesting thing to talk about. It elevates the mentality." And that gets us to Fred Van Dyke, somebody I've long been meaning to revisit here in the Joint, a surfer with zero comp wins to his name but a towering reputation for individual style, and a keen if convoluted interest in the sport's collective mentality. One of my all-time favorite people in surfing. Van Dyke, who died in 2015 at age 86, was bright and funny, sensitive, and more than a little tortured. Longtime EOS readers know that I have written about him often (here and here and most of all here). Yet I have somehow managed to carry this project all the way to 2025 without posting the article Van Dyke is most famous for—the 1968 LIFE feature where Fred describes his big-wave fellows as "latent homosexuals."

He went there! He repeats the phrase three times, in fact, so clearly this was something Fred wanted to lean into. But because nobody, and I mean nobody, heard the word "latent," or bothered to unpack what Freudian Fred was actually trying to say—that the North Shore big-wave crew was made up of adult-aged men living more like boys, seeking only the approval of boys, and were not interested in women in any meaningful way—because nobody got past "homosexual," in other words, the LIFE article blew up spectacularly in Van Dyke's face. "I went surfing the weekend the magazine came out," he later said. "Guys were kicking their boards at me, calling me a faggot, screaming and yelling about what a terrible thing it was."

Fred was 39 in 1968, and had been living and surfing in Hawaii since 1955. As explained in the vivid opening paragraph of the LIFE article, he was as hardcore as they come:

Surfing is what's happening. There's nothing else for me. On a red-hot glassy day of surf I don't care who stands in my way. I will surf. Maybe I've got to lie, cut out on my job, anything. Something snaps inside me. I get diarrhea. My pulse goes out of control. Responsibility, society—it can all get lost. The surf's up and that's where you'll find me.

Now this is way before we get to the latent homosexual bit, and you can see where Van Dyke is actually aiming, before he hijacked his own article. He's going to describe, in detail, the cost of being a dedicated rider of big waves. Or any waves, actually, big or small. Fred wants a reckoning not just on the sport, but himself. The thing Van Dyke has loved and chased since landing in Hawaii—the rush, the recognition, the status—has become a trap. Fred and everyone around him, as explained in the LIFE article, is stunted, vain, shallow, and yes Van Dyke oversteps by speaking for the entire group, but every arrow he fires lands on or near the target, and some are dead-on bullseyes.

Except for the fact that none of Fred's big-wave colleagues, as far as I know, were having sex with each other. "Latent homosexual," in other words, derailed his entire argument.

Van Dyke was still living and surfing on the North Shore throughout the 1970s, and I would bet my collection of Surf Guides that he at least met and conversed with Tom Parrish. I wonder in fact if there was some kind of philosophic laying on of hands. This is Fred in 1968, but it could be Tom in 2025: "There are guys who are fanatically engrossed [in] winning contests, getting sponsored by clothing companies, posing for the cameras. What keeps them hung up on this?" Van Dyke answers his own question. The "hang-ups," as we all said in 1968, were manifest and coming at us from every direction: TV violence, pushy parents, too much emphasis on "crushing" opponants, not enough on fun for fun's sake. Some surfing purists (the sport's unobtrusive "Thoreau-like beings," as Van Dyke puts it) were not warped by these forces. Most were. Fred especially.

I was a slave to the recognition group; I had an insatiable appetite for being recognized as one of the top surfers. I spent hundreds of dollars on surfing pictures of myself. I searched for years for the perfect board, the one that would catapult me to instant glory. And then one night I stood in front of an audience in California. I was being introduced, to 800 people, as a big-wave rider from Hawaii. I looked into the sea of faces, all surfers. I smelled the booze and cigarettes. I saw the lust for prominence in their faces. I thought: Is this what it is all about? Is this why I pushed to the top?

Van Dyke gives us a zinger of an ending. He describes the seasonal influx of surfers to the North Shore each November. Some of these young hopefuls, he says, stay for a week or two, recognize that the scene is less than healthy, turn around and fly home. Others remain. "Many of those who stick it out are the latent homosexuals, and some of them never grow out of it. I know. I was one of them, once."

So that's Fred Van Dyke, surf-shackles broken and free at last, right? Not a chance.

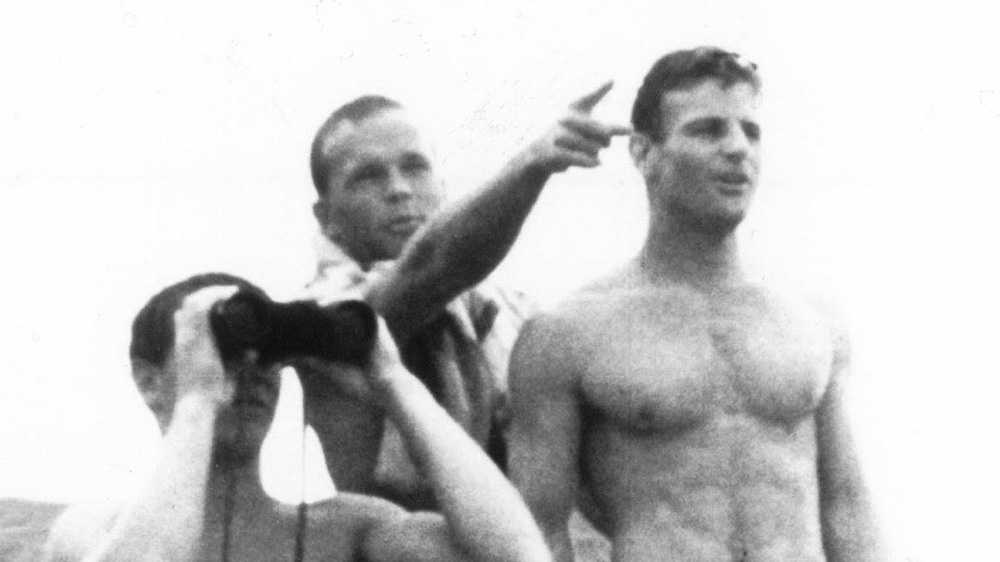

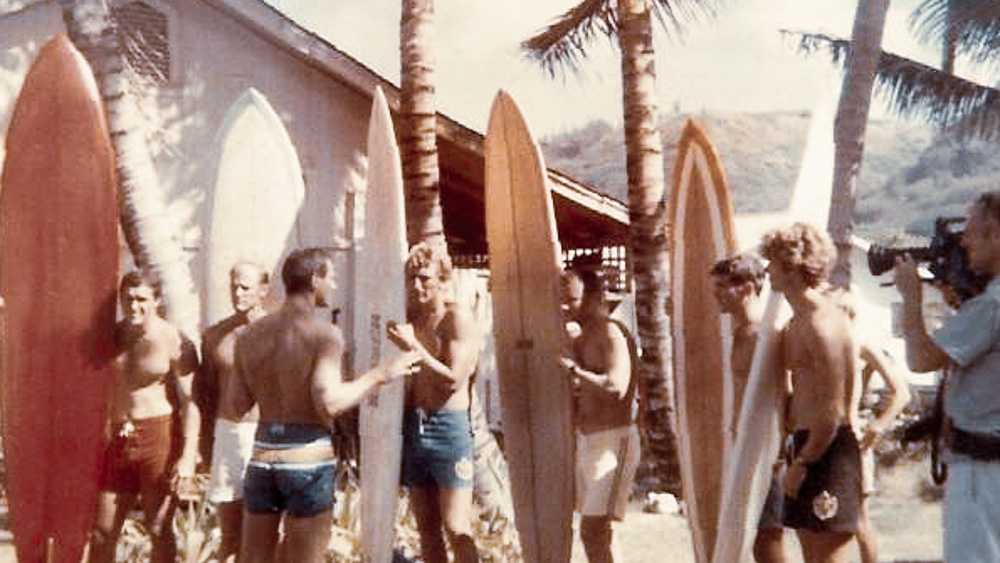

Even as he worked on the LIFE article, Van Dyke was cofounding the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational, which he ran for 11 straight years, starting in 1965. Fame, cameras, trophies, prize money—the Duke event was cutting edge on all that and more, and Van Dyke was at the center. (That's Fred, third from left, directing the 1969 Duke.)

Fred, I think, would be the first to laugh, ruefully, at how the newly-elevated version of himself as presented in LIFE clashes with the mic-holding fame-machine-operating version of himself at the Duke contest. I imagine him scrabbling, defensively, for Walt Whitman's Little Book of Quotations. "Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself."

That line always strikes me as a perfect little rubric of wisdom—except when it sounds like a massive copout, and I will ride that last burst of amibiguity out the door.

Thanks for reading and see you next week!

Matt

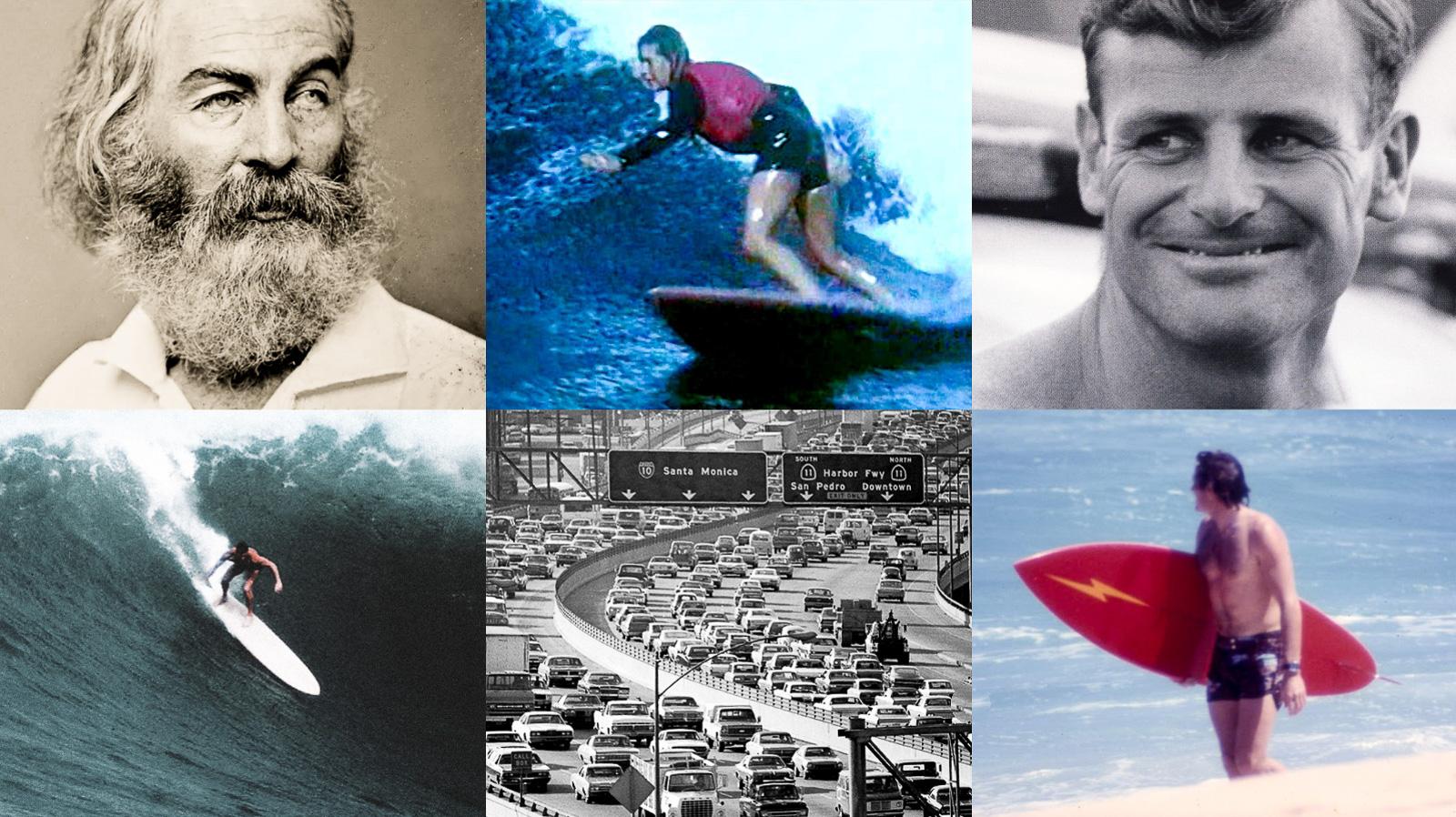

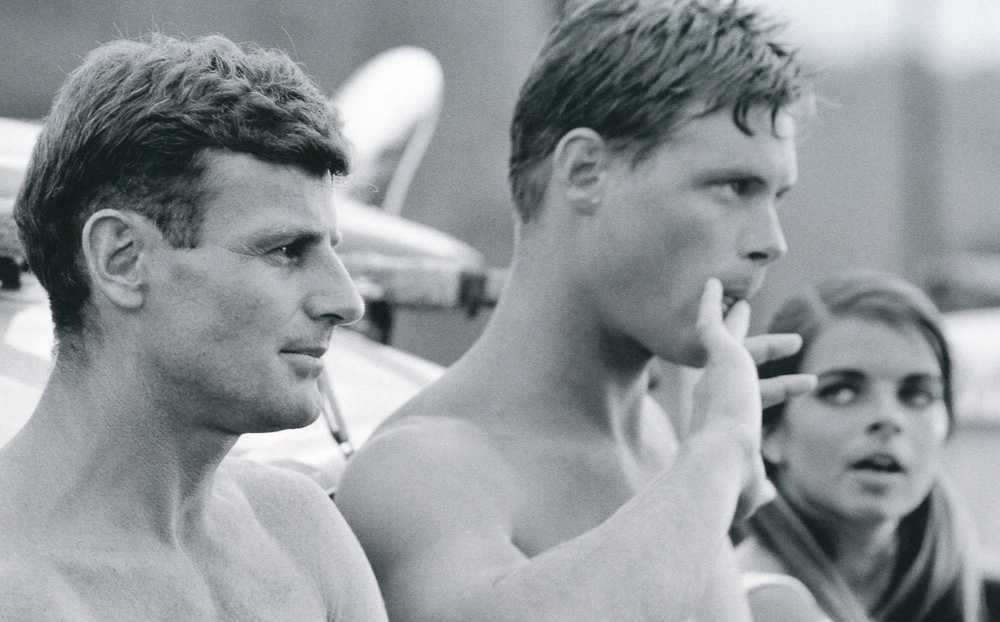

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Walt Whitman; Margo Godfrey, 1970 world titles; Fred Van Dyke, 1965, photo by Ron Church; Tom Parrish, 1978; LA freeway traffic; Van Dyke at Sunset, by John Severson. Tom Parrish, around 1975. Makaha International, late 1950s, photo by Clarence Maki. Four grabs from Blue Cool: Joyce Hoffman, Sharron Weber, unknown, Margo Godfrey. Fred Van Dyke on right, Buzzy Trent pointing, photo by Bud Browne. Van Dyke at Sunset. Van Dyke, left, with Paul Gebauer and unidentified woman, photo by Church. Van Dyke and contestants at the 1969 Duke contest.]