SUNDAY JOINT, 7-27-2025: GOING MAN-ON-MAN WITH MYSELF OVER THE '77 STUBBIES CLASSIC

Hey All,

The last thing to get cut from a recent Joint featuring Phyllis O'Donell was her quote about the '74 Australian Titles, held at Burleigh Heads. O'Donell was 37, the other competitors were almost without exception in their teens or early 20s. "They kept holding the event back," O'Donell later recalled, "waiting for the surf to improve."

Sitting around that morning, all we did was eat, eat, eat. Finally the surf got a little better and the contest started. I had my board and we were going out off the rocks. A wave came along and I sat down on the rocks; I was so full I couldn't get up. I sat there with whitewater all over me going, “You silly old bird, what are you doing?" It was just after that I decided to give it up. I'd had enough [of competing]—11 years of it. I knew it was time to quit.

That's pretty much the way I've felt about spotlighting surf contests here in the Joint the last couple of years. The further removed I am from my own time as a competitor (1970s) or surf-comp reporter (1980s), and the more time I spend looking at the sport in full, the less value contests seem to have.

Even the milestone events are shrinking, and let's loop that thought back to Burleigh, to what is often cited as the original pro tour milestone event, the 1977 Stubbies Classic.

The world circuit had debuted a year earlier with all the grace of a Chevy Chase SNL cold open. Nine-man heats. Steep entry fees, except when the event paid you just to show up. Two different judging systems juggled throughout the year. "Repercharge" heats, whatever those were, and something called a "semi-main" which was different from a semifinal.

Great intentions all around, but 1976 was a DIY hoot, mostly made up on the fly, as much pratfall as it was professional.

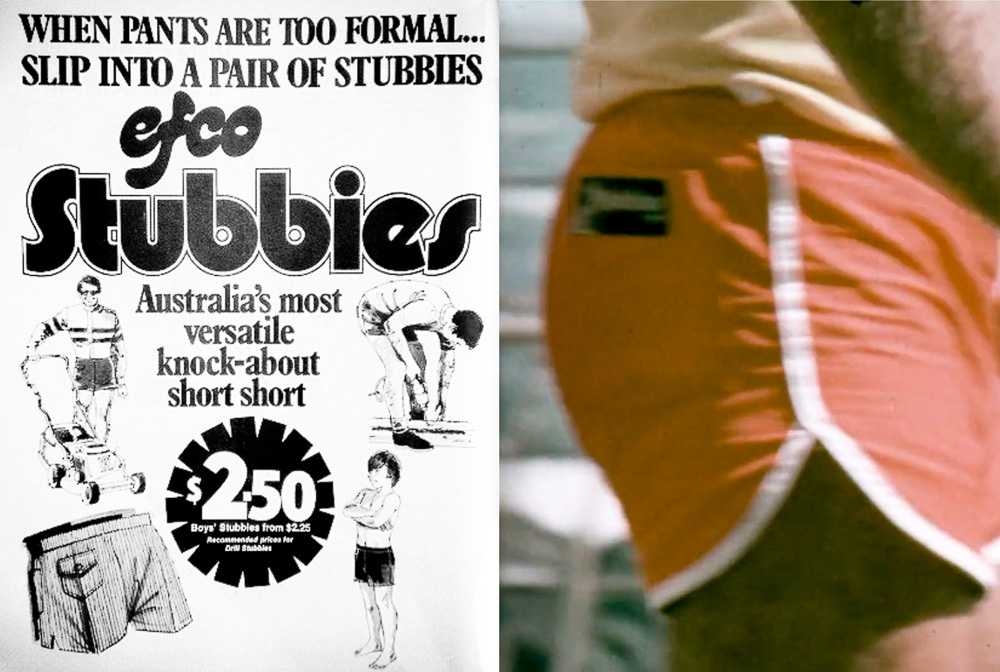

The debut Stubbies Surfing Classic, which opened the 1977 tour, seemed to change all that. The contest was sponsored by EFCO, a 35-year-old Queensland-based company famous for its popular line of minimalist-inseam work shorts (Stubbies, which is also slang for a bottled beer; few things in Australia are more than a degree or two separated from beer), and EFCO's first, boldest move was to hire former Aussie champion and Gold Coaster Peter Drouyn to not only run the event but do so in a new and exciting way. Drouyn's first move, in turn, was to choose Burleigh as the contest site. EFCO put up $12,300 in prizemoney, the biggest purse in surfing history at that point—the Pipeline Masters that year, for comparison, was worth $5,100.

The first thing to know about the 1977 Stubbies is that the waves absolutely pumped. Start to finish, seven straight days of long, hollow, high-performance four-to-six-foot point surf. It was so good and so non-stop that Drouyn actually called a rest day halfway through, even though the surf was still firing. "God knows I need a rest day," writer Phil Jarratt wrote in his Stubbies coverage. "I can't begin to imagine how the guys out in the water are feeling."

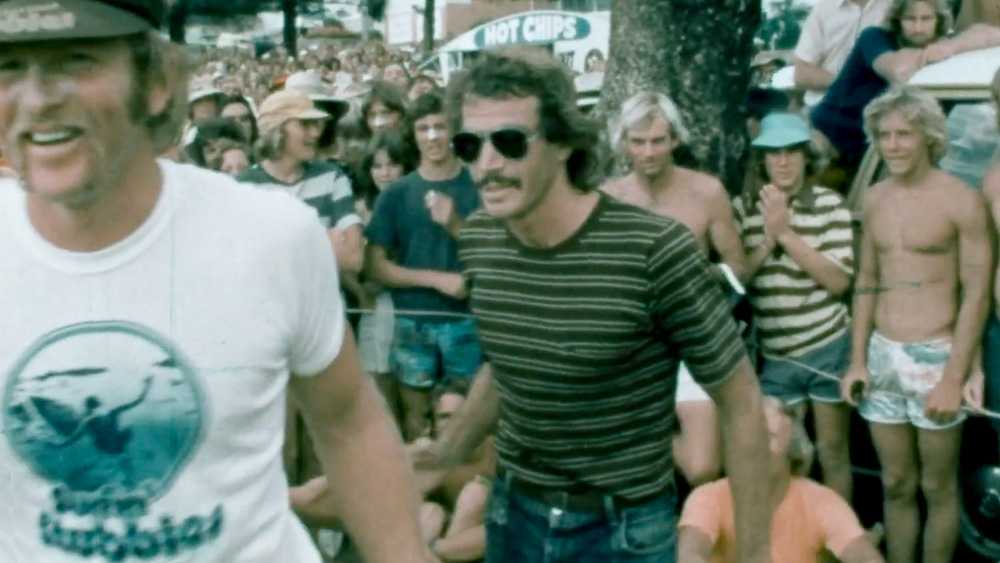

Stubbies' advance work on behalf of the contest was first-rate and widespread (Drouyn wisely played up the Hawaii-Aussie feud from the previous winter), spectators turned out by the tens of thousands, the late-summer weather was hot and sunny, contest organization was tight, smooth, orderly. Altogether, a big leap forward from the world tour standard up to that point. "I'll tell you when we knew things were happening," Shaun Tomson later recalled. "Standing on the point at Burleigh, watching the man-on-man Stubbies, in perfection surf. It was like pro surfing was being born right before our eyes."

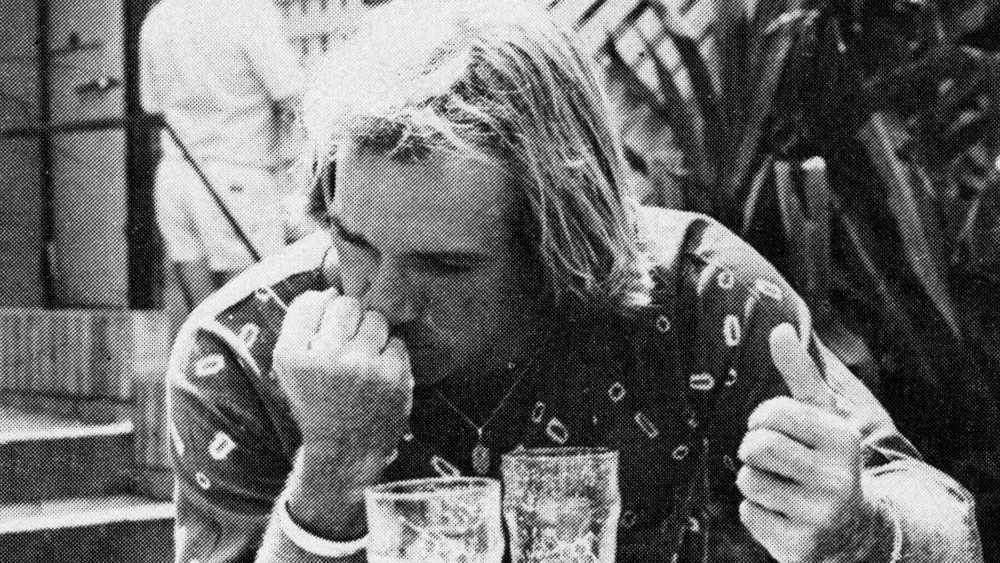

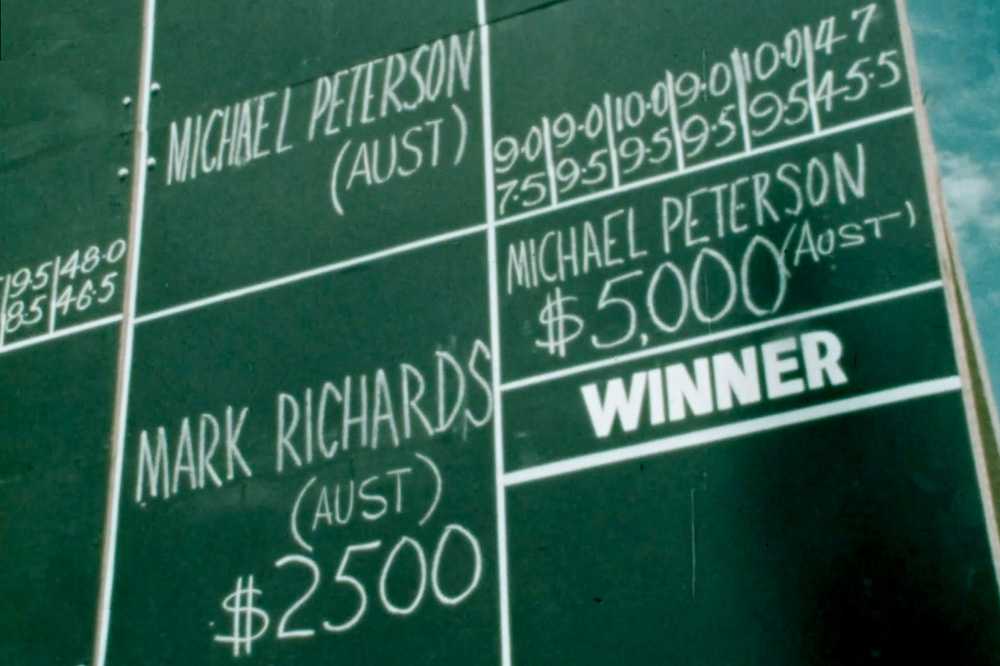

Tomson, who would go on to take the 1977 world title, lost his Stubbies semifinal to Mark Richards, who in turn lost the final to hometown antihero Michael Peterson—a last hurrah for Peterson, whose life and career were already being hollowed out by drug use and mental illness. Everybody involved—surfers, organizers, spectators—went home that final afternoon sunburned, thrilled, and exhausted. If you know anything about world tour history, and don't have the '77 Stubbies somewhere on your Top Five list of best-ever contests, then you don't in fact know anything about world tour history. "Stubbies was Great, Mate!" was the title of Surfing magazine's contest report, and no one argued.

Yet there are some conspicuous nits to pick here, starting with Peter Drouyn, who I have mixed feelings about, and who is somehow underrated and overrated at the same time.

Google and AI and all various and sundry surf-related websites will tell you otherwise, so I'm throwing pebbles at a fortress here, but Peter Drouyn did not invent the paired bracket-style format (we called it "man-on-man" back in the day), nor did the format debut at the Stubbies. Rick Rasmussen beat Jim Cartland in the finals of the '74 US Championships, Tiger Makin beat Mike Purpus in the finals of the '71 Malibu AAAA, and basically everybody in the pro game already knew about and loved the two-surfer format, except that it doubled the time required to run an event and was therefore mostly ignored. Here is a theory: Drouyn himself put it out there that man-on-man heats began at the Stubbies, just so we'd all forget that the thing he was really invested in, the brainchild Peter thought would be a full game-changer, was something he called "effective cheating," which meant a surfer could earn bonus points for dropping in or otherwise ruining his competitor's wave. Read Drouyn's entertaining but ridiculous explanation here. Basically, he wanted to see surfers fight. As in actual fights, on the beach. Drouyn literally kissed his own fists while saying, more serious than joking, I think, "the important thing is that they [the surfers] can beat each other up."

Effective cheating was tried a few times during the Stubbies, but there were no fights, no heats were won or lost on tactical drop-ins, and the whole idea was scrapped forever before the judging towers were broken down and hauled off off the point.

What Drouyn did not get credit for at the Stubbies, and should have—and you could plug this forgotten idea right into the 2026 Challenger Series, as an experiment—is the way points were awarded. In brief, each judge, at the end of a heat, gave just a single overall number, on a 1-to-10 scale, to each competitor. If the winning surfer was impressive but not mind-blowing, for example, a judge might score him a 7.5. The same judge would award a score to the loser based on how much that surfer's performance fell short of the winner. At the end of each heat, the five judges' scores were read out one after the other, like a boxing match, then tallied for a final score. Richards and Peterson had an absolute screamer of a final. Peterson 47, Richards 45.5.

Another thing the Stubbies got right, although again this wasn't a new thing, was to do away with any losers' rounds. This meant the oversized Hawaiian team that came storming into Queensland looking to crack some Aussie heads—metaphorically speaking, or maybe not—were halted almost as soon as they got out of customs. The Aikau brothers, Bobby Owens, Owl Chapman, Mark Foo, and Dennis Pang, were all one-and-done in the Trials. Reno Abellira, Michael Ho, and Rory Russell all lost in the opening round of the Main Event. Nobody whinged or complained. Some drove to Bells for the next event, some flew home. Point being, in 1977 and 2025, losers rounds are for losers.

In more ways than anybody cares to remember today, though, the 1977 Stubbies was in fact not so far removed from pro surfing in 1976 or before. More cash, better promo, improved formatting, sure. But look close and you could still see the Elmer's Glue and thumbtacks. Top-billed Free Ride star and soon-to-be world champ Shaun Tomson's name is misspelled repeatedly on the Stubbies on-site scoreboard, with "THOMPSON" in white chalk all-cap letters growing bigger and bigger as he advanced to the pointy end of the bracket. Many people involved with the Stubbies, as with events of the past, wore more than one hat, in ways that fell somewhere between dodgy and bush league. World tour cofounder Randy Rarick was also a Stubbies competitor (he lost to Wayne Bartholomew). Jack Shipley, head judge, was also part-owner of Lightning Bolt, which meant he was a primary sponsor for at least a half-dozen Stubbies invitees. Reigning world champion Peter Townend was also working the Burleigh beat as a contest reporter. (This is a good place to point out that while Drouyn was mostly and deservedly lauded for his job as Stubbies director, he never again served as a contest official. Drouyn did, however, return to Burleigh in '78 as a Stubbies competitor—losing straight away to Cheyne Horan.)

Finally, the least-remarkable, most-predictable flaw with the '77 Stubbies is that the women pros were left out completely. Beach girls in crochet bikinis were everywhere you looked at Burleigh that week, but no Oberg, Boyer, Sunn, or Poppler, which I suppose is just effective cheating by other means. Stubbies' boys-only policy was retrograde even by Aussie standards. The Sydney-based Surfabout went coed in '77. Bells did so way back in '64. Stubbies grudgingly added a women's division in '78, then dropped it for the next six years.

My take on the debut Stubbies Classic is that it very much earned its front and center position within the gaudy little roadside attraction that is professional surfing. Not because of Drouyn. And not because of the format, or the money, or the massive crowd. But because the surf was excellent. As it was, so it shall be. If Teahupoo is 10-foot and breathing fire next month for the Tahito Pro, cancel everything and pull the shades, I'm watching all day. It its three-foot and sideshore, never mind, I'll wait for JP Currie's BeachGrit recap.

Great waves, great contest. We're not splitting the atom here.

Thanks for reading and see you next week!

Matt

[Photo grid, clockwise from top left: Stubbies winner Michael Peterson; Ian Cairns, second round heat at Burleigh; Stubbies scoreboard; finals day crowd; rock jump at Burleigh. Lineup on opening day of the contest, photo by Dan Merkel. Stubbies ad. Semifinalist Shaun Tomson, photo by Merkel. Mark Richards and Michael Peterson, just prior to finals. Peter Drouyn, photo by Martin Tullemans. Final results on the scoreboard. Peterson cutback. Peterson just after the finals. Stubbies spectators.]